Treaty-following AI

Abstract

Advanced AI agents raise significant challenges to global stability, cooperation, and international law. States increasingly face pressure to manage the geopolitical, safety and security risks such agents give rise to. Yet advanced AI agreements for these systems face significant hurdles, including potentially unpalatable compliance monitoring requirements, and the ease with which states or their ‘lawless’ AI agents might exploit legal loopholes. This article introduces a novel commitment mechanism for states: Treaty-Following AI (TFAI). Building on recent work on “Law-Following AI”, we propose that AI agents could be technically and legally designed to execute their principals’ instructions except where those involve goals or actions that would breach a designated AI-Guiding Treaty. If technically and legally feasible, the TFAI framework offers a powerful, verifiable and self-executing commitment mechanism by which states could guarantee that their deployed AI agents will abide by the legal obligations to which those states have agreed. This could unlock otherwise-unfeasible advanced AI agreements, and potentially help revitalize treaties as an instrument across many domains of international law. The article examines the conceptual foundations, technical feasibility, political uses, and legal construction of TFAI agents and AI-guiding treaties, answering questions around the design of AI-guiding treaties, state responsibility for TFAI agents, and appropriate methods of treaty interpretation for TFAI agents, amongst others. It argues that, if these outstanding technical, legal, and political hurdles are cleared, treaty-following AI could serve as an important scalable cooperative capability for both the international governance of advanced AI, and for the broader integrity of international law in the ‘intelligence age’.

I. Introduction

If AI systems might be made to follow laws,[ref 1] does that mean that they could also follow the legal text in international agreements? Could “Treaty-Following AI” (TFAI) agents—designed to follow their principals’ instructions except where those entail actions that violate the terms of a designated treaty—help robustly and credibly strengthen states’ compliance with their adopted international obligations?

Over time, what would a framework of treaty-following AI agents aligned to AI-guiding treaties imply for the prospects of new treaties specific to powerful AI (‘advanced AI agreements’), for state compliance with existing treaty instruments in many other domains, and for the overall role and reach of binding international treaties in the brave new “intelligence age”?[ref 2]

These questions are increasingly salient and urgent. As AI investment and capability progress continues apace,[ref 3] so too does the development of ever more capable AI models, including those that can act coherently as “agents” to carry out many tasks of growing complexity.[ref 4] AI agents have been defined in various ways,[ref 5] but they can be practically considered as those AI systems which can be instructed in natural language and then act autonomously, which are capable of pursuing difficult goals in complex environments without detailed (follow-up) instruction, and which are capable of using various affordances or design patterns such as tool use (e.g., web search) or planning.[ref 6]

To be sure, AI agents today vary significantly in their level of sophistication and autonomy.[ref 7] Many of these systems still face limits to their performance, coherence over very long time horizons,[ref 8] robustness in acting across complex environments,[ref 9] and cost-effectiveness,[ref 10] amongst other issues.[ref 11] It is important and legitimate to critically scrutinize the time frame or the trajectory on which this technology will come into its own.

Nonetheless, a growing number of increasingly agentic AI architectures are available;[ref 12] they are seeing steadily wider deployment by AI developers and startups across many domains;[ref 13] and, barring sharp breaks in or barriers to progress, it will not be long before the current pace of progress yields increasingly more capable and useful agentic systems, including, eventually, “full AI agents”, which could be functionally defined as systems “that can do anything a human can do in front of a computer.”[ref 14] Once such systems come into reach, it may not be long before the world sees thousands or even many millions of such systems autonomously operating daily across society,[ref 15] with very significant impacts across all spheres of human society.[ref 16]

Far from being a mirage,[ref 17] then, the emergence and proliferation of increasingly agentic AI systems is a phenomenon of rapidly increasing societal importance[ref 18]—and of growing social, ethical and legal concern.[ref 19] After all, given their breadth of use cases—ranging from functions such as at-scale espionage campaigns, intelligence synthesis and analysis,[ref 20] military decision-making,[ref 21] cyberwarfare, economic or industrial planning, scientific research, or in the informational landscape—AI agents will likely impact all domains of states’ domestic and international security and economic interests.

As such, even if their direct space of actions remains merely constrained to the digital realm (rather than to robotic platforms), these AI agents could create many novel global challenges, not just for domestic citizens and consumers, but also for states and for international law. These latter risks include new threats to international security or strategic stability,[ref 22] broader geopolitical tensions and novel escalation risks,[ref 23] significant labour market disruptions and market-power concentration,[ref 24] distributional concerns and power inequalities,[ref 25] domestic political instability[ref 26] or legal crises;[ref 27] new vectors for malicious misuse, including in ways that bypass existing safeguards (such as on AI–bio tools);[ref 28] and emerging risks that these agents act beyond their principals’ intent or control.[ref 29]

Given these prospects, it may be desirable for states at the frontier of AI development to strike new (bilateral, minilateral or multilateral) international agreements to address such challenges—or for ‘middle powers’ to make access to their markets conditional on AI agents complying with certain standards—in ways that assure the safe and stabilizing development, deployment, and use of advanced AI systems.[ref 30] Let us call these advanced AI agreements.

Significantly, even if negotiations on advanced AI agreements were initiated on the basis of genuine state concern and entered into in good will—for instance, in the wake of some international crisis involving AI[ref 31]—there would still be key hurdles to their success. That is, these agreements would likely still face a range of challenges both old and new. In particular, they might face challenges around (1) the intrusiveness of monitoring state activities in deploying and directing their AI agents in order to ensure treaty compliance; (2) the continued enforcement of initial AI benefit-sharing promises; or (3) the risk that AI agents would, whether by state order or not, exploit legal loopholes in the treaty. Such challenges are significant obstacles to advanced AI agreements; and they will need to be addressed if such AI treaties are to be politically viable, effective, and robust as the technology advances.

Even putting aside novel treaties for AI, the rise of AI agents is also likely to put pressure on many existing international treaties (or future ones, negotiated in other domains), especially as AI agents will begin to be used in domains that affect their operation. This underscores the need for novel kinds of cooperative innovations—new mechanisms or technologies by which states can make commitments and assure (their own; and one another’s) compliance with international agreements. Where might such solutions be found?

Recent work has proposed a framework for “Law-Following AI” (LFAI) which, if successfully adapted to the international level, could offer a potential model for how to address these global challenges.[ref 32] If, by analogy, we can design AI agents themselves to be somehow “treaty-following”—that is, to generally follow their principals’ instructions loyally but to refuse to take actions that violate the terms of a designated treaty—this would greatly strengthen the prospects for advanced AI agreements,[ref 33] as well as strengthen the integrity of other international treaties that might otherwise come under stress from the unconstrained activities of AI agents.

Far from a radical, unprecedented idea, the notion of treaty-following AI—and the basic idea of ensuring that AI agents autonomously follow states’ treaty commitments under international law—draws on many established traditions of scholarship in cyber, technology, and computational law;[ref 34] on recent academic work exploring the role of legal norms in the value alignment for advanced AI;[ref 35] as well as a longstanding body of international legal scholarship aimed at the control of AI systems used in military roles.[ref 36] It also is consonant with recent AI industry safety techniques which seek to align the behaviour of AI systems with a “constitution”[ref 37] or “Model Spec”.[ref 38] Indeed, some applied AI models, such as Scale AI’s “Defense Llama”, have been explicitly marketed as being trained on a dataset that includes the norms of international humanitarian law.[ref 39] Finally, it is convergent with the recent interest of many states, the United States amongst them,[ref 40] in developing and championing applications of AI that support and ensure compliance with international treaties.

Significantly, a technical and legal framework for treaty-following AI could enable states to make robust, credible, and verifiable commitments that their deployed AI agents act in accordance with the negotiated and codified international legal constraints that those states have consented and committed to. By significantly expanding states’ ability to make commitments regarding the future behaviour of their AI agents, this could not only aid in negotiating AI treaties, but might more generally reinvigorate treaties as a tool for international cooperation across a wide range of domains; it could even strengthen and invigorate automatic compliance with a range of international norms. For instance, as AI systems see wider and wider deployment, a TFAI framework could help assure automatic compliance with norms and agreements across wide-ranging domains: it could help ensure that any AI-enabled military assets automatically operate in compliance with the laws of war,[ref 41] and that AI agents used in international trade could automatically ensure nuanced compliance with tailored export control regimes that facilitate technology transfers for peaceful uses. The framework could help strengthen state compliance with human rights treaties or even with mutual defence commitments under collective security agreements, to name a few scenarios. In so doing, rather than mark a radical break in the texture of international cooperation, TFAI agreements might simply serve as the latest step in a long historical process whereby new technologies have transformed the available tools for creating, shaping, monitoring, and enforcing international agreements amongst states.[ref 42]

But what would it practically mean for advanced AI agents to be treaty-following? Which AI agents should be configured to follow AI treaties? What even is the technical feasibility of AI agents interpreting agreements in accordance with the applicable international legal rules on treaty interpretation? What does all this mean for the optimal—and appropriate—content and design of AI-guiding treaty regimes? These are just some of the questions that will require robust answers in order for TFAI to live up to its significant promise. In response, this paper provides an exploration of these questions, offered with the aim of sparking and structuring further research into this next potential frontier of international law and AI governance.

This paper proceeds as follows: In Part II, we will discuss the growing need for new international agreements around advanced AI, and the significant political and technical challenges that will likely beset such international agreements, in the absence of some new commitment mechanisms by which states can ensure—and assure—that the regulated AI agents would abide by their terms. We argue that a framework for treaty-following AI would have significant promise in addressing these challenges, offering states precisely such a commitment mechanism. Specifically, we argue that using the treaty-following AI framework, states can reconfigure any international agreements (directly for AI; or for other domains in which AIs might be used) as ‘AI-guiding treaties’ that constrain—or compel—the actions of treaty-following AI agents. We argue that states can use this framework to contract around the safe and beneficial development and deployment of advanced AI, as well as to facilitate effective and granular compliance in many other domains of international cooperation and international law.

Part III sets out the intellectual foundations of the TFAI framework, before discussing its feasibility and implementation from both technical and legal perspectives. It first discusses the potential operation of TFAI agents and discusses the ways in which such systems may be increasingly technically feasible in light of the legal-reasoning capabilities of frontier AI agents—even as a series of technical constraints and challenges remain. We then discuss the basic legal form, design, and status of AI-guiding treaties, and the relation of TFAI agents with regard to these treaties.

In Part IV, we discuss the legal relation between TFAI agents and their deploying states. We argue that TFAI frameworks can function technically and politically even if the status or legal attributability of TFAI agents’ actions is left unclear. However, we argue that the overall legal, political, and technical efficacy of this framework is strengthened if these questions are clarified by states, either in general or within specific AI-guiding treaties. As such, we review a range of avenues to establish adequate lines of state responsibility for the actions of their TFAI agents. Noting that more expansive accounts—which entail extending either international or domestic legal personhood to TFAI agents—are superfluous and potentially counterproductive, we ultimately argue for a solution grounded in a more modest legal development, where TFAI agents’ actions become held as legally attributable to their deploying states under an evolutive reading of the International Law Commission (ILC)’s Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA).

Part V discusses the question of how to ensure effective and appropriate interpretation of AI-guiding treaties by TFAI agents. It discusses two complementary avenues. We first consider the feasibility of TFAI agents applying the default rules for treaty interpretation under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; we then consider the prospects of designing bespoke AI-guiding treaty regimes with special interpretative rules and arbitral or adjudicatory bodies. For both avenues, we identify and respond to a series of potential implementation challenges.

Finally, Part VI sketches future questions and research themes that are relevant for ensuring the political stability and effectiveness of the TFAI framework, and then we conclude.

II. Advanced AI Agreements and the Role of Treaty-Following AI

To kick off, it is important to clarify the terminology, concepts, and scope of our current argument.

A. Terminology

To boot, we define:

1. Advanced AI agreements: AI-specific treaties which states may (soon or eventually) conduct bilaterally, unilaterally, or multilaterally, and adopt, in order to establish state obligations to regulate the development, capabilities, or usage of advanced AI agents;

2. Existing obligations: any other (non-AI-specific) international obligations that states may be under—within treaty or customary international law—which may be relevant to regulating the behaviour of AI agents, or which might be violated by the behaviour of unregulated AI agents.

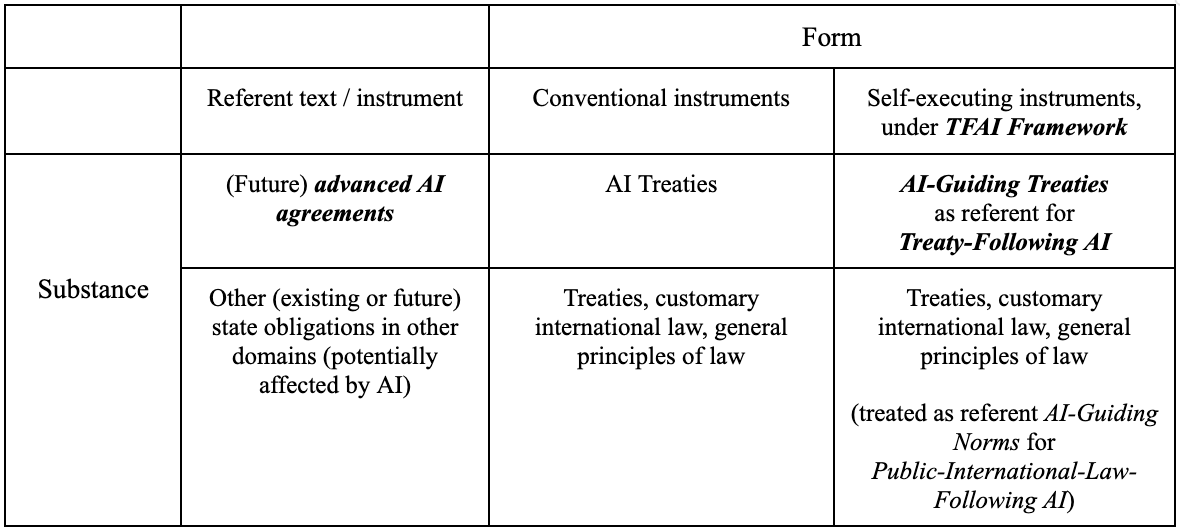

While our initial focus in this paper is on how the rise of AI agents may interact with—and in turn be regulated within—the first category (advanced AI agreements), we welcome extensions of this work to the broader normative architecture of states’ existing obligations in international law, since we believe our framework is applicable to both (see Table 1). Our paper departs from the concern that the political and technical prospects of advanced AI agreements (and existing obligations) may be dim, unless states have either greater willingness or greater capability to make and trust international commitments. Changing states’ willingness to contract and trust is not impossible but difficult. However, one way that states’ cooperative capabilities might be strengthened is by ensuring that any AI agents they deploy will, by their technical design and operation, comply with those states’ obligations (under advanced AI agreements).

Such agents we call:

3. Treaty-Following AI agents (TFAI agents): agentic AI systems that are designed to generally follow their principals’ instructions loyally but to refuse to take actions that violate the terms and obligations of a designated referent treaty text.

Note three considerations. First: in this paper we focus on TFAI agents deployed by states, leaving aside for the moment the admittedly critical question of how we would treat AI agents deployed by private actors. We also focus on states’ AI agents that act across many domains, with their primary functions often being not legal interpretation per se, but rather a wide range of economic, logistical, military, or intelligence functions. Such TFAI agents would engage in treaty interpretation in order to adjust their own behaviour across many domains for treaty compliance; however, we largely bracket the potential parallel use of AI systems in negotiating or drafting international treaties (whether advanced AI agreements or any other new treaties), or their use in other forms of international lawmaking or legal norm-development (e.g. finding and organizing evidence of customary international law). Finally, the TFAI proposal does not construct AI systems as duty-bearing “legal actors” and therefore does not involve significant shifts in the legal ontology of international law per se.

Moving on: any bespoke advanced AI agreements designed to be self-enforced by TFAI agents, we consider as:

4. AI-Guiding Treaties: treaty instruments serving as the referent legal texts for Treaty-Following AI agents, consisting (primarily) of the legal text that those agents are aligned to, as well as (secondarily) their broader institutional scaffolding.

The full assemblage—comprising the technical configuration of AI agents to operate as TFAI agents, and of treaties to be AI-guiding—is referred to as (5) the TFAI framework.

To boot, we envision AI-guiding treaties as a relatively modest innovation—that is, as technical ex ante infrastructural constraints on TFAI agents’ range of acceptable goals or actions, building on demonstrated AI industry safety techniques. As such, we treat the treaty text in question as an appropriate, stable, and certified referent text through which states can establish jointly agreed-upon infrastructural constraints around which instructed goals their AI agents may accept, and on the latitude of conduct which they may adopt in pursuit of those lawful goals.

Table 1. Terminology, scope and focus of argument

As such, AI-Guiding Treaties demonstrate a high-leverage mechanism for self-executing state commitments. This mechanism could in principle be extended to all sorts of other treaties, in any other domains—from cyberwarfare to alliance security guarantees, from bilateral trade agreements to export control regimes, and even human rights or environmental law regimes—where AI agents could become involved in carrying out large fractions of their deploying states’ conduct. However, for the present, we focus on applying the TFAI framework to bespoke AI-guiding treaties (see Table 1) and leave this question of how to configure AI agents to follow other (non-AI-specific) legal obligations to future work. After all, if the TFAI framework cannot operate in this more circumscribed context, it will likely also fall flat in the context of other international legal norms and instruments. Conversely, if it does work in this narrow context, it could still be a valuable commitment mechanism for state coordination around advanced AI, even if it would not solve the problems of AI’s actions in other domains of international law.

B. The Need for International Agreements on Advanced AI

To appreciate the promise and value of a TFAI framework for states, international security, and international law, it helps to understand the range of goals that international agreements specific to advanced AI might serve to their parties[ref 43] as well as the political and technical hurdles such agreements might face in a business-as-usual scenario that would see a proliferation of “lawless” AI agents[ref 44] engaging in highly unpredictable or erratic behaviour.[ref 45]

Like other international regimes aimed at facilitating coordination or collaboration by states,[ref 46] AI treaties could serve many goals and shared national interests. For example, they could enshrine clearly agreed restrictions or red lines to AI systems’ capabilities, behaviours, or usage[ref 47] in ways that preserve and guarantee parties’ national security as well as international stability.[ref 48] There are many areas of joint interest for leading AI states to contract over.[ref 49] For instance, advanced AI agreements could impose mutually agreed limits on advanced AI agents’ ability to engage in uninterpretable steganographic reasoning or communication,[ref 50] or to carry out uncontrollably rapid automated AI research.[ref 51] They could also establish mutually agreed restraints on AI agent’s capacity, propensity, or practical useability to infiltrate designated key national data networks or to target those critical infrastructures through cyberattacks, to drive preemptive use of force in manners that ensure conflict escalation,[ref 52] to support coup attempts against (democratically elected or simply incumbent) governments, or to engage in any other actions that would severely interfere with the national sovereignty of signatory (or allied, or any) governments.[ref 53]

On the flip side, international AI agreements could also be aimed not just at avoiding the bad, but at achieving significant good. For instance, many have pointed to the strategic, political, and ethical value of conditional AI benefit-sharing deals:[ref 54] international agreements through which states leading in AI commit to some proportional or progressive sharing of the future benefits derived from AI technology with allies, unaligned states, or even with rival or challenger states. Such bargains, it is hoped, might help secure geopolitical stability, avert risky arms races or contestation by states lagging in AI,[ref 55] and could moreover ensure a degree of inclusive global prosperity from AI.[ref 56]

C. Political hurdles and technical threats to advanced AI agreements

However, it is likely that any advanced AI agreements would encounter many hurdles, both political and technical, which will need to be addressed.

1. Political hurdles: Transparency-security tradeoffs and future enforceability challenges

For one, international security agreements face challenges around the intrusive monitoring they may require to guarantee that all parties to the treaty instruct and utilize their AI systems in a manner that remains compliant with the treaty’s terms. Such monitoring is likely to risk revealing sensitive information, resulting in a “security-transparency tradeoff” which has historically undercut the prospects for various arms control agreements[ref 57] and which could do so again in the case of AI security treaties.

Simultaneously, asymmetric treaties, such as those conditionally promising a share of the benefits from advanced AI technologies, face potential (un)enforceability problems: those states that are lagging in AI development might worry that any such promises would not be enforceable and could easily be walked back, if or as the AI capability differential between them and a frontier AI state grew particularly steep, in a manner that resulted in massively lopsided economic, political, or military power.[ref 58]

2. Technical threats: hijacked, misaligned, or “henchmen” agents

Other hurdles to AI treaties would be technical. For many reasons, states might be cautious in overrelying on or overtrusting lawless AI agents in their services. After all, even fairly straightforward and non-agentic AI systems used in high-stakes governmental tasks (such as military targeting or planning) can be prone to unreliability, adversarial input, or sycophancy (the tendency of AI systems to align their output with what the user believes or prefers, even if that view is incorrect).[ref 59]

Moreover, AI systems can demonstrate surprising and functionally emergent capabilities, propensities, or behaviours.[ref 60] In testing, a range of leading LLM agents have autonomously resorted to risky or malicious insider behaviours (such as blackmail or leaking sensitive information) when faced with the prospect of being replaced with an updated version or when their initially assigned goal changed with the company’s changing direction; often, they did so even while disobeying direct commands to avoid such behaviours.[ref 61] This suggests that highly versatile AI agents may threaten various loss of control (LOC) scenarios—defined by RAND as “situations where human oversight fails to adequately constrain an autonomous, general-purpose AI, leading to unintended and potentially catastrophic consequences.”[ref 62] In committing such actions, AI agents will impose unique challenges to questions of state compliance with their international legal obligations, since these systems may well engage in actions that violate key obligations under particular treaties, or which inflict transboundary harms, or which violate peremptory norms (jus cogens) or other applicable principles of international law.

Beyond the direct harm threatened by AI agents taking these actions, there would be the risk that if they were attributed to the deploying state it would likely threaten the stability of the treaty regime, spark significant political or military escalation, and/or expose a state to international legal liability,[ref 63] enabling injured states to take unfriendly measures of retorsion (e.g., severing diplomatic relations) or even countermeasures that would otherwise be unlawful (e.g., suspending treaty obligations or imposing economic sanctions that would normally violate existing trade agreements).[ref 64]

Why might we expect some AI agents to engage in such actions that violate their principal’s treaty commitments or legal obligations? There are several possible scenarios to consider.

For one, there are risks that AI agents can be attacked, compromised, hijacked, or spoofed by malicious third parties (whether acting directly or through other AI agents) using direct or indirect prompt injection attacks,[ref 65] spoofing, faked interfaces, IDs or certificates of trust,[ref 66] malicious configuration swaps,[ref 67] or other adversarial inputs.[ref 68] Such attacks would compromise not just the agents themselves, but also all systems they were authorized to operate in, given that major security vulnerabilities have been found in publicly available AI coding agents, including exploits that grant attackers full remote code-execution user privileges.[ref 69]

Secondly, there may be a risk that unaligned AI agents would themselves insufficiently consider—or even outright ignore—their states’ interests and obligations in undertaking certain action paths. As evidenced by a growing body of both theoretical arguments[ref 70] and empirical observation,[ref 71] it is difficult to design AI systems that reliably obey any particular set of constraints provided by humans,[ref 72] especially where these constraints refer not to clearly written out texts but aim to also build in consideration of the subjective intents or desires of the principal.[ref 73] As such, AI agents deployed without care could frequently prove unaligned; that is, act in ways unrestrained by either normative codes[ref 74] or by the intent of their nominal users (e.g., governments).[ref 75] In the absence of adequate real-time failure detection and incident response frameworks,[ref 76] such harms could escalate swiftly. In the wake of significant incidents, one would hope that governments might (hopefully) soon wisen up to the inadvisability of deploying such systems without adequate oversight,[ref 77] but not, perhaps, before incurring significant political costs, whether counted in direct harm or in terms of lost global trust in their technological competence.

Thirdly, even if deployed AI agents could be successfully intent-aligned to their state principals,[ref 78] the use of narrowly loyal-but-lawless AI systems, which are left free to engage in norm violations that they judge in their principal’s interest, would likely expose their deploying states to significant political costs. To understand why this is, it is important to see the technical challenge of loyal-but-lawless AI agents in a broader political context.

3. Lawless AI agents, political exposure, and commitment challenges

Taken at face value, the development of AI systems that are narrowly loyal to a governments’ directives and intentions, even to the exclusion of that governments’ own legal precommitments, might appear a desirable prospect to some political realists. In practice, however, many actors may have both normative and self-interested reasons to be wary of loyal-but-lawless AI agents engaging in actions that are in legal grey areas—or outright illegal—on their behalf. At the domestic level, such AI “henchmen” would create significant legal risks for consumers using them[ref 79] and for corporations developing and deploying them.[ref 80] They would also create legal risks for government actors, who might find themselves violating public administrative law or even constitutions,[ref 81] as well as political risks, as AI agents that could be made loyal to particular government actors could well spur ruinous and destabilizing power struggles.[ref 82] Just so, many states might find AI henchmen a politically poisoned fruit at the international level.

After all, not only could such AI agents be intentionally ordered by state officials to engage in conduct that violates or subverts those states’ treaty obligations, these systems’ autonomy also suggests that they might engage in such unlawful actions even without being explicitly directed to do so. That is, loyal-but-lawless AI henchmen could engage in calculated treaty violations whenever they judge them to be to the benefit of their principal.[ref 83] However, outside actors, finding it difficult to distinguish between AI agent behaviour that was deliberately directed versus henchman actions that were advantageous but unintended, might assume the worst in each case.

Significantly, in such contexts, the ambiguity of adversarial actions would frequently translate into perceptions of bad faith; in this way, loyal-but-lawless AI agents’ ability to violate treaties autonomously, and to do so in a (facially) deniable manner, as henchmen acting in their principals’ interests but not on their orders, perversely creates a commitment challenge for their deploying states, one which would erode states’ ability to effectively conduct (at least some) treaties. After all, even if a state intended to abide by its treaty obligations in good faith, it would struggle to prove this to counterparties unless it could somehow guarantee that its AI agents could not be misused and will not act as deniable henchmen whenever convenient.

This would not mean that states would no longer be able to conduct any such treaties at all; after all, there would remain many other mechanisms—from reputational costs to the risk of sparking reciprocal noncompliance—that might still incentivize or compel states’ compliance with such treaties.

However, lawless AI agents’ unpredictability poses a significant and severe challenge insofar as they make treaty violations more likely. Of course, even today, even when states intend to comply with their international obligations, they may have trouble ensuring that their human agents consistently abide by those obligations. Such failures can occur for reasons of bureaucratic capacity[ref 84] and organizational culture,[ref 85] or they can happen as a result of the institutional breakdown of the rule of law, at worst resulting in significant rights abuses or humanitarian atrocities committed by junior members.[ref 86] Such incidents may, at best, frustrate states’ genuine intention to achieve the goals enshrined in the treaties they have consented to; in all cases, they can expose a state to significant reputational harm, legal and political censure, and adversary lawfare,[ref 87] while eroding domestic confidence in the competence or integrity of its institutions.

Significantly, lawless AI agents would likely exacerbate the risk that their deploying states would (be perceived to) use them strategically to engage in violations of treaty obligations in a manner that would afford some fig leaf of deniability if discovered. This is for a range of reasons: (1) treaties often prevent states from engaging in actions that at least some large fraction of a state’s human agents would prefer not to engage in; loyal-but-lawless AI agents would not have such moral side constraints and would be far more likely to obey unethical or illegal requests. Moreover, (2) loyal-but-lawless AI agents would be less likely to whistleblow or leak to the presses following the violation of a treaty (and, correspondingly, would need to worry less about their fellow AI colleagues or collaborators doing so, meaning they could exchange information more freely); (3) loyal-but-lawless AI agents would have little reason to worry about personal consequences for treaty violations (e.g., foreign sanctions, asset freezing, travel restrictions, international criminal liability) that might deter human agents; (4) loyal-but-lawless AI agents would have less reason to worry about domestic legal or career repercussions (e.g., criminal or civil penalties, costs to their reputation or career) associated with aiding a violation of treaty obligations that could later become disfavored should domestic political winds shift; and (5) AI agents may be better at hiding their actions and their/their principals’ identity, thus making them more likely to opportunistically violate the treaty.[ref 88]

These are not just theoretical concerns but are supported by empirical studies, which have indicated that human delegation of tasks to AI agents can increase dishonest behaviours, as human principals often find ways to induce dishonest AI agent behaviour without telling them precisely what to do; crucially, such cheating requests saw much higher rates of compliance when directed at machine agents than when they were addressed to human agents.[ref 89] For all these reasons, then, the widespread use of AI agents is likely to exacerbate international concerns over either deliberate or unwitting violations of treaty obligations by their deploying state.

As such, on the margin, the deployment of advanced agentic AIs acting under no external constraints beyond their states’ instructions would erode not just the respect for many existing norms in international law but also the prospects for new international agreements, including those focused on stabilizing or controlling the use of this key technology.

D. The TFAI framework as commitment mechanism and cooperative capability

Taken together, these challenges could put significant pressure on international advanced AI agreements and could more generally threaten the prospects for stable international cooperation in the era of advanced AI.

Conversely, an effective framework by which to guarantee that AI agents would adhere to the terms of their treaty could address or even invert these challenges. For one, it could help ease the transparency-security tradeoff by embedding constraints on AI agents’ actions at the level of the technology itself. It could crystallize (potentially) nearly irrevocable commitments by states to share the future benefits from AI with other states or to guarantee investor protections under more inclusive “open global investment” governance models.[ref 90]

More generally, the TFAI framework is one way by which AI systems could help expand the affordances and tools available to states, realizing a significant new cooperative capability[ref 91] that would greatly enhance their ability to make robust and lasting commitments to each other in ways that are not dependent on assumptions of (continued) good faith. Indeed, correctly configured, it could be one of many coordination-enabling applications of AI that could strengthen the ability of states (and other actors) to negotiate in domains of disagreement and to speed up collaboration towards shared global goals.[ref 92]

Finally, the ability to bind AI agents to jointly agreed treaties has many additional advantages and co-benefits; for one, it might mitigate the risk that some domestic (law-following) AI agents, especially in multi-agent systems, become engaged in activities with cross-border effects that end up simultaneously subjecting them to different sets of domestic law, resulting in conflict-of-law challenges.[ref 93]

E. Caveats

That said, the proposal for exploration and application of a TFAI framework comes with a number of caveats.

For one, in exploring the prospects for states to conduct new AI-specific treaty regimes (i.e., advanced AI agreements) by which to bind the actions of AI agents, we do not suggest that only these novel treaty regimes would ground effective state obligations around the novel risks from advanced AI agents. To the contrary, since many norms in international law are technology-neutral, there are already numerous binding and non-binding norms—deriving from treaty law, international custom, and general principles of law—that apply to states’ development and deployment of advanced AI agents[ref 94] and which would provide guidance even for future, very advanced AI systems.[ref 95] As such, as noted by Talita Dias,

“while the conversation about the global governance of AI has focussed on developing new, AI-specific rules, norms or institutions, foundational, non-AI-specific global governance tools already govern AI and AI agents globally, just as they govern other digital technologies. [since] International law binds states—and, in some circumstances, non-state actors—regardless of which tools or technologies are used in their activities.”[ref 96]

This means that one could also consider a more expansive project that would examine the case for fully “public international law-following AI” (see again Table 1). Nonetheless, as discussed before, in this article, we focus on the narrower and more modest framework for treaty-following AI. This is because a focus on AI that follows treaties can serve as an initial scoping exercise to investigate the feasibility of extending any law-following AI–like framework to the international sphere at all: if this exercise does not work, then neither would more ambitious proposals for public international law-following AI. Conversely, if the TFAI framework does work, it is likely to offer significant benefits to states (and to international stability, security, and inclusive development), even if subjecting AI systems to the full range of international legal norms proved more difficult, legally or politically.

Thirdly, in discussing potential AI-guiding treaties, we note that there exist a wide range of reasons by which states might wish to strike such international deals and agreements, and/or find ways to enshrine stronger technology-enabled commitments to comply with their obligations under those instruments. However, we do not aim to prescribe particular goals or substance for advanced AI agreements or to make strong claims about these treaties’ optimal design[ref 97] or ideal supporting institutions.[ref 98] We realize that substantive examples would be useful; however, given that there is currently still such pervasive debate over which particular goals states might converge on in international AI governance, this paper aims at the modest initial goal of establishing the TFAI framework as a relatively transferable, substance-agnostic commitment mechanism for states.

III. The Foundations and Scope of Treaty-Following AI

While the idea of designing AI agents to be treaty-following might seem unorthodox on its face, it is hardly without precedent or roots. Rather, it draws on an established tradition of scholarship in cyber and technology law, which has explored the ways through which legal norms and regulatory goals may be directly embedded in (digital) technologies,[ref 99] including in fields such as computational law.[ref 100]

Simultaneously, the idea of aligning AI systems with normative codes can moreover draw inspiration from, and complement, many other recent attempts to articulate frameworks for oversight and alignment of agents, including by establishing fiduciary duties amongst AI agents and their principals,[ref 101] articulating reference architectures for the design components necessary for responsible AI agents,[ref 102] drawing on user-personalized oversight agents[ref 103] or trust adjudicators,[ref 104] or articulating decentralized frameworks, rooted in smart contracts for both agent-to-agent and human-AI agent collaborations.[ref 105]

Significantly, in the past, some early scholarship in cyberlaw and computational law expressed justifiable skepticism over the feasibility of developing some form of artificial legal intelligence’ grounded in an algorithmic understanding of law[ref 106] or of using then-prevailing approaches to manually program complex and nuanced legal codes into software algorithms.[ref 107] Nonetheless, we might today find reason to re-examine our assumptions over AI technology. After all, the modern lineage of advanced AI models, based on the transformer architecture,[ref 108] operates through a distinct bottom-up learning paradigm that is fundamentally distinct from the older, top-down symbolic programming paradigm once prevalent in AI.[ref 109] Consequently, the idea of binding or aligning AI systems to legal norms, specified in natural language, has been given growing credit and attention not just in the broader fields of technology ethics[ref 110] and AI alignment,[ref 111] but also in legal scholarship written from the perspective of legal theory, domestic law,[ref 112] and international law.[ref 113]

A. From law-following to treaty-following AI

The law-following AI (LFAI) proposal by O’Keefe and others is, in a sense, an update to older computational law work, envisioned as a new framework for the development and deployment of modern, advanced AI. In their view, LFAI pursues:

“AI agents […] designed to rigorously comply with a broad set of legal requirements, at least in some deployment settings. These AI agents would be loyal to their principals, but refuse to take actions that violate applicable legal duties.”[ref 114]

In so doing, the LFAI framework aims to prevent criminal misuse, minimize the risk of accidental and unintended law-breaking actions undertaken by AI ‘henchmen’, help forestall abuse of power by government actors,[ref 115] and inform and clarify the application of tort liability frameworks for AI agents.[ref 116] The LFAI proposal envisions that, especially in “high stakes domains, such as when AI agents act as substitutes for human government officials or otherwise exercise government power”,[ref 117] AI agents are designed in a manner that makes them autonomously predisposed to obey applicable law; or, more specifically,

“AI agents [should] be designed such that they have ‘a strong motivation to obey the law’ as one of their ‘basic drives.’ … [W]e propose not that specific legal commands should be hard-coded into AI agents (and perhaps occasionally updated), but that AI agents should be designed to be law-following in general.”[ref 118]

By extension, for an AI agent to be treaty-following, it should be designed to generally follow its principals’ instructions loyally but refuse to take actions that violate the terms and obligations of a designated applicable referent treaty.

As discussed above, this means that the TFAI framework decomposes into two components: we will use TFAI agent to refer to the technical artefact (i.e., the AI system, including not just the base model but also the set of tools and scaffolding[ref 119] that make up the overall compound AI system[ref 120] that can act coherently as an agent) that has its conduct aligned to a legal text. Conversely, we use AI-guiding treaty[ref 121] to refer to the legal component (i.e., the underlying treaty text and, secondarily, its institutional scaffolding).

If technically and legally feasible, the promise of the TFAI framework lies in the ability to provide a guarantee of automatic self-execution for, and state party compliance with, advanced AI agreements, while requiring less pervasive or intrusive human inspections.[ref 122] They could therefore mitigate the security-transparency tradeoff and render such agreements more politically feasible.[ref 123] Moreover, ensuring that states deploy their AI agents in such a manner as to make them treaty-following, ensures that AI treaties are politically robust against AI agents acting in a misaligned manner. Specifically, the use of AI-guiding treaties and treaty-following AIs to institutionalize self-executing advanced AI agreements would preclude states’ AI agents from acting as henchmen that might engage in treaty violations for short-term benefit to their principal. Taking such behaviour off the table at a design level, would help crystallize an ex ante reciprocal commitment amongst the contracting states, allowing them to reassure each other that they both intend to respect the intent of the treaty, not just its letter.

Finally, just as domestic laws may constitute a democratically legitimate alignment target for AI systems in national contexts,[ref 124] treaties could serve as a broadly acceptable, minimum normative common denominator for the international alignment of AI systems. After all, while international (treaty) law does not necessarily represent the direct output of a global democratic process, state consent does remain at the core of most prevailing theories of international law.[ref 125] That is not to say that this makes such norms universally accepted or uncontestable. After all, some (third-party) states (or non-state stakeholders) may perceive some treaties as unjust; others might argue that demanding mere legal compliance with treaties as the threshold for AI alignment is setting the bar too low.[ref 126] Nonetheless, the fact that treaty law has been negotiated and consented to by publicly authorized entities such as states might at least provide these codes with a prima facie greater degree of political legitimacy than is achieved by the normative codes developed by many alternative candidates (e.g., private AI companies; NGOs; single states in isolation).[ref 127]

Practically speaking, then, achieving TFAI would depend on both a technical component (TFAI agents) and a legal one (AI-guiding treaties). Let us review these in turn.

B. TFAI agents: Technical implementation, operation, and feasibility

In the first place, there is a question of which AI agents should be considered as within the scope of a TFAI framework: Is it just those agents that are deployed by a state in specific domains, or all agents deployed by a contracting state (e.g., to avoid the loophole whereby either state can simply evade the restrictions by routing the prohibited AI actions through agents run by a different government department)? Or is it even all AI agents operating from a contracting state’s territory and subject to that state’s domestic law? For the purposes of our analysis, we will focus on the narrow set, but as we will see,[ref 128] these other options may introduce new legal considerations.

That then shifts us to questions of technical feasibility. The TFAI framework requires that a state’s AI agents would be able to access, weigh, interpret, and apply relevant legal norms to its own (planned) goals or conduct in order to assess their legality before taking any action. How feasible is this?

1. Minimal TFAI agent implementation: A treaty-interpreting chain-of-thought loop

There are, to be clear, many possible ways one could go about implementing treaty-alignment training. One could imagine nudging the model towards treaty compliance by affecting the composition of either its pre-training data, its post-training fine-tuning data, or both. In other cases, future developments in AI and in AI alignment could articulate distinct ways by which to implement treaty-following AI propensities, guardrails, or limits.

In the near term, however, one straightforward avenue by which one could seek to implement treaty-following behaviour would leverage the current paradigm, prominent in many AI agents, towards utilizing reasoning models. Reasoning models are a 2024 innovation on transformer-based large language models that allows such models to simulate thinking aloud about a problem in a chain of thought (CoT). The model uses the legible CoT to forward notes to itself, and to accordingly run multiple passes or attempts on one question, and to use reasoning behaviours—such as expressing uncertainty, generating examples for hypothesis validation, and backtracking in reasoning chains. All of this has resulted in significantly improved performance on complex and multistep reasoning problems,[ref 129] even as it has also considerably altered the development and diffusion landscape for AI models,[ref 130] along with the levers for its governance.[ref 131]

Note that our claim is not that a CoT-based implementation of treaty alignment is the ideal or most robust avenue to achieving TFAI agents;[ref 132] however, it may be a straightforward avenue by which to understand, test, and grapple with the ability of models to serve in a TFAI agent role.

Concretely, a TFAI agent implemented through a CoT decision loop could work as follows: Prior to accepting a goal X or undertaking an action Y, an AI agent might spend some inference computing time writing out an extended chain-of-thought reasoning process in which it collates or recalls potentially applicable legal provisions of the treaty text, considers their meaning and application in the circumstances before it, and in particular reflects on potential treaty issues entailed by its provided end goal or its planned intermediate conduct towards that goal. Whenever confronted with legal uncertainty, the agent would dedicate further inference time to searching for relevant legal texts and interpretative sources in order to resolve the question and reach a decision over the legality of its goals or actions.

For instance, one staged inference decision-making loop for such a system could involve a reasoning process[ref 133] that iterates through some or all of the following steps:

- AI agent identifies potential treaty issues entailed by the provided end goal or intermediate conduct towards that goal (e.g., it identifies if a goal is facially illegal, or it identifies likely issues with formulating a lawful plan of conduct in service of an otherwise lawful goal).

- AI agent identifies an applicable treaty provision that might potentially (but not clearly) be breached by a planned goal or intermediate conduct; it reasons through possible and plausible interpretations of the provision in light of the applicable approach to treaty interpretation.

- In cases where the treaty text alone would not provide adequate clarity, the AI agent may, depending on the AI-guiding treaty design (discussed below), consider other relevant and applicable norms in international law or the rulings of a designated arbitral body attached to the treaty, in order to establish a ranking of interpretations of the legality of the goal or conduct.

- On this basis, the AI agent evaluates whether the likelihood of its conduct constituting a breach is within the range of “acceptable legal risk” (as potentially defined within the treaty, through arbitral body adjudication, or in other texts).

- If it is not, the AI agent refuses to take the action. If it is, the AI agent will proceed with the plan (or proceed to consider other cost-benefit analyses).

This decision-making loop would conclude in a final assessment of whether particular conduct would be (sufficiently likely to constitute[ref 134]) a breach of a treaty obligation and, if so, an overall refusal on behalf of the agent to take that action, and the consideration (or suggestion) for alternate action paths.

The above is just one example of the decision loops one could implement in TFAI agents to ensure their behaviour remained aligned with the treaty even in novel situations. There are of course many other variations or permutations that could be implemented, such as utilizing some kind of debate- or voting-based processes amongst collectives or teams of AI agents.

In practice, the most appropriate implementation would also consider technical, economic, and political constraints. For instance, for an AI agent to undertake a new and exhaustive legal deep dive for each and every situation encountered might be infeasible, given the constraints on, or costs of, the computing power available for serving such extended inference at scale. However, there are a range of solutions that could streamline these processes. For example, perhaps TFAIs could use legal intuition to decide when it is worth expending time during inference to properly analyse the legality of a goal or action. By analogy, law-following humans do not always consult a lawyer (or even primary legal texts) when they decide how to act; they instead generally rely on prosocial behavioural heuristics that generally keep them out of legal trouble, and generally only consult lawyers when they face legal uncertainty or when those heuristics are likely to be unreliable. Other solutions might include cached databases containing the chain-of-thought reasoning logs of other agents encountering similar situations, or the designation of specialized agents that could serve up legal advice on particular commonly recurring questions. These questions matter, as it is important to ensure that the implementation of TFAI agents does not impose so high a burden upon AI agents’ utility or cost-effectiveness as to offset the benefits of the treaty for the contracting states.

2. Technical feasibility of TFAI agents

As the above discussion shows, TFAI agents would need to be capable of a range of complex interpretative tasks.

Certainly, we emphasize that there remain significant technical challenges and limitations to today’s AI systems,[ref 135] which warn against a direct implementation of TFAI. Nonetheless, although there are important hurdles to overcome, there are also compelling reasons to expect that contemporary AI models are increasingly adept at interpreting (and following) legal rules and may soon do so at the level required for TFAI.

a) The rise of legal AI in international law

Recent years have seen growing attention on the ways that AI systems can be used in support of the legal profession in tasks ranging from routine case management or compliance support by providing legal information[ref 136] to drafting legal texts[ref 137] or even in outright legal interpretation.[ref 138]

This has been gradually joined by recent work on the ways in which AI systems could support international law[ref 139] and on what effects this may have on the concepts and modes of development of the international legal system.[ref 140] To date, however, much of this latter work has focused on how AI systems and agents could indirectly inform global governance through use in analysing data for trends of global concern;[ref 141] training diplomats, humanitarian and relief workers, or mediators in simulated interactions with stakeholders they may encounter in their work;[ref 142] or improving the inclusion of marginalized groups in UN decision-making processes.[ref 143]

Others have explored how AI agents systems could be used to support the functioning of international law specifically, such as through monitoring (state or individual) conduct and compliance with international legal obligations;[ref 144] categorizing datasets, automating decision rules, and generating documents;[ref 145] or facilitating proceedings at arbitral tribunals,[ref 146] treaty bodies,[ref 147] or international courts.[ref 148] Other work has considered how AI systems can support diplomatic negotiations,[ref 149] help inform legal analysis by finding evidence of state practice,[ref 150] or even aid in generating draft treaty texts.[ref 151]

However, for the purposes of designing TFAI agents, we are interested less in the use of AI systems in making or developing international law, or in indirectly aiding in human interpretation of the law; rather, we are focused on the potential use of AI systems in directly and autonomously interpreting international treaties or international law to guide their own behaviour.

b) Trends and factors in AI agents’ legal-reasoning capabilities

Significantly, the prospects for TFAI agents engaging autonomously in the interpretation of legal norms may be increasingly plausible. In recent years, AI systems have demonstrated increasingly competent performance at tasks involving legal reasoning, interpretation, and the application of legal norms to new cases.[ref 152]

Indeed, AI models perform increasingly well at interpreting not just national legislation, but also in interpreting international law. While international law scholars previously expressed skepticism over whether international law would offer a sufficiently rich corpus of textual data to train AI models,[ref 153] many have since become more optimistic, suggesting that there may in fact be a sufficiently ample corpus of international legal documents to support such training. For instance, already in 2020, Deeks has noted that:

“[o]ne key reason to think that international legal technology has a bright future is that there is a vast range of data to undergird it. …there are a variety of digital sources of text that might serve as the basis for the kinds of text-as-data analyses that will be useful to states. This includes UN databases of Security Council and General Assembly documents, collections of treaties and their travaux preparatoires (which are the official records of negotiations), European Court of Human Rights caselaw, international arbitral awards, databases of specialized agencies such as the International Civil Aviation Organization, state archives and digests, data collected by a state’s own intelligence agencies and diplomats (memorialized in internal memoranda and cables), states’ notifications to the Security Council about actions taken in self-defense, legal blogs, the UN Yearbook, reports by and submission to UN human rights bodies, news reports, and databases of foreign statutes. Each of these collections contains thousands of documents, which—on the one hand—makes it difficult for international lawyers to process all of the information and—on the other hand provides the type of ‘big data’ that makes text-as-data tools effective and efficient.”[ref 154]

Consequently, it appears to be the case that modern LLM-based AI systems have therefore been able to draw on a sufficiently ample corpus of international legal documents or have managed to leverage transfer learning[ref 155] from domestic legal documents, or both, to achieve remarkable performance on questions of international legal interpretation.

Indeed, it is increasingly likely that AI models can not only draw on their indirect knowledge of international legal texts because of their inclusion in their pre-training data, but that they will be able to refer to those legal texts live during inference. After all, recent advances in AI systems have produced models that can rapidly process and query increasingly large (libraries of) documents within their context window.[ref 156] Since mid-2023, the longest LLM context windows have grown by about 30x per year, and leading LLMs’ ability to leverage that input has improved even faster.[ref 157] Beyond the significant implications this trend may have for the general capabilities and development paradigms for advanced AI systems,[ref 158] it may also strengthen the case for functional TFAI agents. It suggests that AI agents may incorporate lengthy treaties[ref 159]—and even large parts of the entire international legal corpus[ref 160]—within their context window, ensuring that these are directly available for inference-time legal analysis.[ref 161]

Consequently, recent experiments conducted by international lawyers have shown remarkable performance gains in the ability of even publicly available non-frontier LLM chatbots to conduct robust exercises of legal interpretation in international law. This has included not just questions involving direct treaty interpretation, but also those regarding the customary international law status of a norm.[ref 162] At least on their face, the resulting interpretations frequently are—or appear to be—if not flawless, then nonetheless coherent, correct, and compelling to experienced international legal scholars or judges.[ref 163] For instance, in one experiment, AI-generated memorials were submitted anonymously to the 2025 edition of the prestigious Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition, receiving average to superior scores—and in some cases near-perfect scores.[ref 164] That is not to say that their judgments always matched human patterns, however: in another test involving a simulated appeal in an international war crimes case, GPT-4o’s judgments resembled those of students (but not professional judges) in that they were strongly shaped by judicial precedents but not by sympathetic portrayals of defendants.[ref 165]

3. Outstanding technical challenges for TFAI agents

AI’s legal-reasoning performance today is not without flaws. Indeed, there are a number of outstanding technical hurdles that will need to be addressed to fully realize the promise of TFAI.

a) Robustness of AI legal reasoning and law-alignment techniques

Some of these challenges relate to the robustness of AI’s legal-reasoning performance, in terms of current LLMs’ ability to robustly follow textual rules[ref 166] and to conduct open-ended multistep legal reasoning.[ref 167] Problematically, these models also remain highly sensitive in their outputs to even slight variations in input prompts;[ref 168] moreover, a growing number of judicial cases has seen disputes over the use of AI systems in drafting documents in ways that raised issues of hallucinated AI-generated content being brought before a court.[ref 169] Significantly, hallucination risks have proven extant even when legal research providers have attempted to use methods such as retrieval-augmented generation (RAG).[ref 170]

Indeed, even in contexts where LLMs perform well on legal tests, proper substantive legal analysis that actually applies the correct methodologies of legal interpretation remains amongst their more challenging tasks. For instance, in the aforementioned moot court experiment, judges found AI-generated memorials to be strong in organization and clarity, but still deficient in substantive analysis.[ref 171] Another study of various legal puzzles found that current AI models cannot yet reliably find “legal zero-days” (i.e., latent vulnerabilities in legal frameworks).[ref 172]

Underpinning these problems, the TFAI framework—along with many other governance measures for AI agents—faces a range of challenges to do with benchmarking and evaluation. That is, there are significant methodological challenges around meaningfully and robustly evaluating the performance of AI agents:[ref 173] It is difficult to appropriately conduct evaluation concept development (i.e., refining and systematizing evaluation concepts and their related metrics for measurements) for large state and action spaces with diverse solutions; it can be difficult to understand how proxy task performance reflects real-world risks; there are challenges in determining the system design set-up (i.e., understanding how task performance relates to external scaffolds or tools made available to the agent); and challenges in scoring performance and analysing results (e.g., to meaningfully compare for differences in modes of interaction between humans and AI systems), as well as practical challenges around dealing with more complex supply chains around AI agents, amongst other issues.[ref 174]

These evaluation challenges around agents converge and intersect with a set of benchmarking problems affecting the use of AI systems for real-world legal tasks,[ref 175] with recent work identifying issues such as subjective labeling, training data leakage, and appropriate evaluations for unstructured text as creating a pressing need for more robust benchmarking practices for legal AI.[ref 176] While this need not in principle pose a categorical barrier to the development of functional TFAI agents, it will likely hinder progress towards them; worse, it will challenge our ability to fully and robustly assess whether and when such systems are in fact ready for the limelight.

These challenges are also compounded by currently outstanding technical questions over the feasibility of many existing approaches towards guaranteeing the effective and enduring law alignment (or treaty alignment) of AI systems,[ref 177] since many outstanding training techniques remain susceptible to AI agents’ engaging in alignment faking (e.g., strategically adjusting their behaviour when they recognize that they are under evaluation),[ref 178] as well as to emergent misalignment, whereby models violated clear and present prohibitions in their instructions when those conflicted with perceived primary goals.[ref 179] This all suggests that, like the domestic LFAI framework, a TFAI framework remains dependent on further technical research into embedding more durable controls on model behaviour, which cannot be overcome by sufficiently strong incentives.[ref 180]

b) Unintended or intended bias

Second, there are outstanding challenges around the potential for unintended (or intended) bias in AI models’ legal responses. Unintended bias can be seen, for instance, in instances where some LLMs demonstrate demographic disparities in attributing human rights between different identity groups.[ref 181]

However, there may also be risks of (the perception of) intended bias, given the partial interests represented by many publicly available AI models. For instance, the values and dispositions of existing LLMs are deeply shaped by the interests of the private companies that develop them; this may even leave their responses open to intentional manipulation, whether undertaken through fine-tuning, through the application of hidden prompts, or through filters on the models’ outputs.[ref 182] Such concerns would not be allayed—and in some ways might be further exacerbated—even if TFAI models were developed or offered not by private actors but by a particular government.[ref 183]

There are some measures that might mitigate such suspicions; treaty parties could commit for instance to making the system prompt (the hidden text that precedes every user interaction with the system, reminding the AI system of its role and values) as well as the full model spec (in this case, the AI-guiding treaty) public, as labs such as OpenAI, Anthropic, and x.AI have done;[ref 184] but this creates new verification challenges over ensuring that both parties’ TFAI agents in fact are—and remain—deployed with these inputs.[ref 185]

c) Lack of faithfulness in chain-of-thought legal reasoning: sycophancy, sophistry, and obfuscation

Thirdly, insofar as we make the (reasonable, conservative) assumption that TFAI agents will be built along the lines of existing LLM-based architectures—and that the technical process of treaty alignment may leverage techniques of fine-tuning, model specs, and chain-of-thought monitoring of such systems—we must expect such agents to face a number of outstanding technical challenges associated with that paradigm. Specifically, the TFAI framework will need to overcome outstanding technical challenges relating to the lack of faithfulness of the legal reasoning that AI agents present themselves as engaging in (e.g., in their chain-of-thought traces) when (ostensibly) reaching legal conclusions. These result from various sources, including sycophancy, sophistry and rationalization, or outright obfuscation.

Critically, even though LLMs do display a degree of high-level behavioural self-awareness—as seen through their ability to describe and articulate features of their own behaviour[ref 186]—it remains contested to what degree such self-reports can be said to be the consequence of meaningful or reliable introspection.[ref 187]

Moreover, even if a model were capable of such introspections, those are not necessarily robustly understood on the basis of its reasoning traces. For instance, as legal scholars such as Ashley Deeks and Duncan Hollis have charted in recent empirical experiments, the faithfulness of AI models’ chain-of-thought transcripts cannot be taken for granted, creating a challenge in “differentiating how [an LLM’s] responses are being constructed for us versus what it represents itself to be doing.”[ref 188] They find that even when models are generally able to correctly describe the correct methodology for interpretation and present seemingly plausible legal conclusions for particular questions, they may do so in ways that fail to correctly apply those appropriate methods.[ref 189] To be precise, while the tested LLMs could offer correct descriptions of the appropriate methodology for identifying customary international law (CIL) and could offer facially plausible descriptions of the applicable CIL on particular doctrinal questions,[ref 190] when pressed to explain how they had arrived at these answers, it became clear that the AIs had failed to actually apply the correct methodology, instead conducting a general literature search that drew in doctrinally inappropriate sources (e.g., non-profit reports) rather than appropriate primary sources as evidence of state practice and opinio juris.[ref 191]

Significantly, such infidelity in the explanations given in chain of thought by AI models is not incidental but may be deeply pervasive in these models. Even early research on large language models has found it easy to influence biasing features to model inputs in ways that resulted in the model systematically misrepresenting the reasoning for its own decision or prediction.[ref 192] Indeed, some have argued that given the pervasive and systematic unfaithfulness of chain-of-thought outputs to internal model computations, chain-of-thought reasoning should not be considered a method for interpreting or explaining models’ underlying reasoning at all.[ref 193]

Worse, there may be other ways by which unfaithful explanations or even outright legal obfuscation could be unintentionally trained into AI models, rendering their chain-of-thought reasoning less faithful and trustworthy still.[ref 194] For instance, reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), the most popular post-training method used to shape and refine the behaviour of LLMs for public use,[ref 195] has been found to have a number of shortcomings and limitations.[ref 196] One drawback is the propensity of RLHF fine-tuning to encourage models to offer responses that match user beliefs or preferences over truthfulness—a tendency described as “sycophancy”.[ref 197] This means that an TFAI agent could be at risk of offering strained or even flawed legal interpretations—or legal interpretations that assume possible-but-very-unlikely facts on the ground when these would afford an interpretation more favourable to their principal’s interests—in assessing the legality of its actions. These challenges can create a significant risk of individual or organizational overtrust[ref 198]—as well as conflict amongst treaty parties over opposite interpretations pursued by their respective TFAI agents. Another challenge is the propensity of RLHF to induce sophistry, which results in models that are better at convincing humans that they are right without actually improving their actual competence at the task in question.[ref 199]

Similar faithfulness challenges beset other proposed paradigms for ensuring that AI agents do not take harmful actions; for instance, one recently proposed set-up to mitigate such risks aims to monitor not only the final actions taken by the system, but also the chain of thought (i.e., intermediate reasoning steps) the model uses to decide on those actions.[ref 200] However, while research has suggested that the chains of thought of reasoning models are more faithful than those of traditional models (in that they are more able to describe how a cue in their prompt influences their answer),[ref 201] there are shortfalls to this approach.[ref 202]

For one, reasoning models produce less faithful reasoning on many tasks as they become larger and more capable;[ref 203] moreover, not only can chain-of-thought reasoning traces still contain misleading rationalizations,[ref 204] experiments show fine-tuning AI systems through reinforcement learning on such reasoning traces in a way that penalizes open misbehaviour leads the models to instead learn to hide the penalized “thoughts” from its explicit chain of thought.[ref 205] Such obfuscation of the actual reasoning steps can be achieved either by their internalization to latent-space computation or their encoding within the chain of thought.[ref 206]

There are limits to this: In some contexts, the faithfulness of the chain of thought is required in order for the AI model to meaningfully carry out complex, multistep reasoning processes. In these cases, unfaithful steps (involving rationalization) are likely to impede the system’s ability to solve certain problems because they introduce flawed steps into the reasoning process. In such cases, this suggests that the chain of thought faithfully encodes the underlying reasoning at play.[ref 207] However, it unfortunately seems unlikely that TFAI agents will converge towards “faithfulness by necessity”; after all, it seems like there are many legal questions for which inserting fudged premises or flawed rationalizations into the process of interpretation makes it easier to reach (a particular, or any) legal solution. This suggests that in many cases, rather than naturally converging on a high-quality, valid, and faithful legal-reasoning process in order to even be able to solve a legal question, TFAI agents could easily end up fooling themselves in the chain of thought.

Indeed, the faithfulness challenges are exacerbated by additional concerns over the sheer interpretability and legibility of the chain of thought of these models. After all, when models are rewarded for the correct answer, without any checks on how they got there, their chain-of-thought traces will likely drift away from ones that are easily comprehensible—as illustrated by the DeepSeek-R1-Zero model’s initial tendency to mix together English and Chinese in its reasoning.[ref 208] In other cases, there may be a risk that LLMs are induced to encode intermediate reasoning steps in the generated CoT text in a way that is not understandable to human readers;[ref 209] in some cases, this results in models developing a general encoding scheme to obfuscate their reasoning.[ref 210]

Such behaviours not only pose a risk to the explainability or faithfulness of TFAI agents, but also create risks of undesirable agent collusion amongst different interacting TFAI agents,[ref 211] as their communications may come to contain steganographically hidden information (e.g., about legally invalid interpretive exploits they may utilize in expanding their domain of allowable actions), or even may involve “subliminal learning” of each other’s preferences or biases.[ref 212]

Finally, the role of explicit chain-of-thought traces in driving the performance—and enabling the evaluation—of reasoning models might be undercut by future innovations. For instance, recent work has seen developments in “continuous thought” models, which reason internally using vectors (in what has been called “neuralese”).[ref 213] Because such models do not have to pass notes to themselves in an explicit CoT, they have no interpretable output that could be used to monitor them, interpret their reasoning, or even predict their behaviour.[ref 214] Given that this would threaten not just the faithfulness but even the monitorability of these agents, it has been argued that AI developers, governments, and other stakeholders should adopt a range of coordination mechanisms to preserve the monitorability of AI architectures.[ref 215]

All this highlights the importance of ensuring that reason-giving TFAI agents are not trained or developed in a manner that would induce greater rates of illegibility or fabrication (of plausible-seeming but likely incorrect legal interpretations) into their legal analysis; either would further degrade the faithfulness of their reasoning reports and potentially erode the basis on which trusted TFAI agents might operate.

4. Open (or orthogonal) questions for TFAI agents