Automated Compliance and the Regulation of AI

Abstract

Regulation imposes compliance costs on regulated parties. Thus, policy discourse often posits a trade-off between risk reduction and innovation. Without denying this trade-off outright, this paper complicates it by observing that, under plausible forecasts of AI progress, future AI systems will be able to perform many compliance tasks cheaply and autonomously. We call this automated compliance. While automated compliance has important implications in many regulatory domains, it is especially important in the ongoing debate about the optimal timing and content of regulations targeting AI itself. Policymakers sometimes face a trade-off in AI policy between potentially regulating too soon or strictly (and thereby stifling innovation and national competitiveness) versus too late or leniently (and thereby risking preventable harms). Under plausible assumptions, automated compliance loosens this trade-off: AI progress itself hedges the costs of AI regulation. Automated compliance implies that, for example, policymakers could reduce the risk of premature regulation by enacting regulations that become effective only when AI is capable of largely automating compliance with such regulations. This regulatory approach would also mitigate concerns that regulations may unduly benefit larger firms, which can bear compliance costs more easily than startups can. While regulations can remain costly even after many compliance tasks have become automated, we hope that the concept of automated compliance can enable a more multidimensional and dynamic discourse around the optimal content and timing of AI risk regulation.

Policy Implications

- AI progress will reduce the cost of certain regulatory compliance tasks.

- Policymakers can reduce risks from premature regulation by using “automatability triggers” to stipulate that regulations become effective only when AI tools are capable of automating compliance with such regulations.

- Proper implementation of compliance-automating AI workflows may provide evidence of regulatory compliance.

- Targeted measures can support the development of compliance-automating AI services.

- Automated compliance is most effective when complemented by the responsible automation of regulator-side regulatory and oversight tasks.

Introduction

Few contest that rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities and adoption will require regulatory intervention. Instead, some of the deepest disagreements in AI policy concern the general timing, substance, and purpose of those regulations. The stakes, most agree, are high.1 Those more concerned with risks from AI worry about, for example, risks from misuse of AI systems to make weapons of mass destruction,2 from strategic destabilization,3 and from loss of control of advanced AI systems that are not aligned with humanity.4 In turn, some individuals with this perspective have called for a more aggressive regulatory posture aimed at reducing the odds of worst-case scenarios.5 Those who are focused on the benefits of AI systems point out that there is a large amount of uncertainty as to the likelihood of these risks and regarding best practices for risk mitigation.6 They also champion the potential of such systems to drive innovations in medicine and other areas of science,7 to supercharge economic growth more generally,8 and to enable strategic applications that could determine the balance of global power.9 The regulatory posture of these individuals tends to be more hands-off out of a concern for early regulations entrenching existing actors and perhaps leading to technological path dependence.10

Both perspectives simultaneously find some support from the observed characteristics of currently deployed AI systems11 but are also necessarily based on a forecast of a large number of uncertain variables, including the trajectories of AI capabilities, societal adaptation, international relations, and public policy. As a result of these disagreements and uncertainties, perspectives on the appropriate course of action range widely, from, at one pole, unilateral or coordinated “pausing” of AI progress,12 to, at the other pole, deregulation and acceleration of AI progress.13 We might call this the proregulatory–deregulatory divide.14

The foregoing is an oversimplified sketch of what is in fact a much more multidimensional debate. Innovation and regulation are not always zero-sum.15 People—including both authors of this article—tend to hold a combination of proregulatory and deregulatory views depending on the exact AI policy issue. Many policies are preferable under both views; other policies complicate or straddle the divide. Others question whether proregulation versus deregulation is even the right frame for this debate at all.16 Semantics aside, the fundamental tension between proregulatory and deregulatory approaches to AI policy is, in many cases, real. Indeed, at the risk of oversimplifying our own views, the authors generally locate themselves on opposite sides of the proregulatory–deregulatory divide.17

There are many causes of the proregulatory–deregulatory divide, including empirical disagreements about the likely impacts of future AI systems and normative disagreements about how to value different policy risks or outcomes. We do not attempt to resolve these here. We do, however, note one reason to think that the trade-offs between the proregulatory and deregulatory approaches may not remain as harsh as they presently seem: future AI systems will likely be able to automate many compliance tasks, including many required by AI regulations.18 We can call these compliance-automating AIs. Compliance-automating AIs will be able to, for example, perform automated evaluations of AI systems, compile transparency reports of AI systems’ performance on those evaluations, monitor for safety and security incidents, and provide incident disclosures to regulators and consumers.19

Compliance-automating AIs deserve a larger role in the discussion of regulation across all economic sectors.20 But their implications for regulation of AI itself warrant special attention. This is for two reasons. First, as detailed above, the stakes of AI policy are immense, with weighty considerations on both sides of the proregulatory–deregulatory divide. Compliance-automating AI will affect the costs of AI regulation and therefore be an increasingly important input into the overall cost-benefit analysis of proposed regulations of this important sector. Second, AI policy is unique in that compliance-automating AI can both influence and be influenced by AI policy. As mentioned, the availability of compliance-automating AI will influence the cost-benefit profile of many AI policies, and therefore, one hopes, whether and when such policies are implemented. But AI policies, in turn, will also influence whether and when compliance-automating AI is developed. The interaction between compliance-automating AI and policy is therefore much more complicated in AI than in other policy domains.

This paper proceeds as follows. In Part I, we briefly note the potentially high costs associated with regulatory compliance. In Part II, we survey how current AI policy proposals attempt to manage compliance costs. In Part III, we introduce the concept of automated compliance: a prediction that, as AI capabilities advance, AI systems will themselves be capable of automating some regulatory compliance tasks, leading to reduced compliance costs.21 In Part IV, we note several implications of automated compliance for the design of AI regulations. First, we propose the novel concept of automatability triggers: regulatory mechanisms that specify that AI regulations become effective only when automation has reduced the costs to comply with regulations below a predetermined level. Second, we note how AI policies could use automated compliance as evidence of compliance. Third, we identify several tasks policymakers, entrepreneurs, and civic technologists could take to accelerate automated compliance. Finally, we note the possible synergies between automated compliance and automated governance.

I. Regulatory Costs

Regulation can be very costly to the regulated party, the regulator, and (therefore) the economy as a whole. While a holistic survey of the potential costs associated with regulation is well beyond the scope of this paper,22 we briefly note some data points indicating the potential costs of regulation.

Compliance costs are perhaps the most easily observable costs. By “compliance costs,” we mean “the costs that are incurred by businesses . . . at whom regulation may be targeted in undertaking actions necessary to comply with the regulatory requirements, as well as the costs to government of regulatory administration and enforcement.”23 This includes both administrative costs (e.g., the costs associated with producing and processing paperwork required by regulation) and substantive costs (e.g., the costs associated with reengineering a product to comply with substantive standards imposed by regulation).24

To take just a few examples:

- The state of California estimated that initial compliance costs for the California Consumer Privacy Act totaled approximately $55 billion.25

- A large share of the increased costs of generating nuclear power is due to increased (and changing) safety regulations.26 For example, quality control and quality assurance requirements cause there to be a “nuclear premium” for commodity components of nuclear power plants.27 The nuclear premium has been estimated at 23% of the cost of concrete and 41% of the cost of steel in nuclear plants.28

- Financial crime compliance costs in the US and Canada are estimated at $61 billion,29 becoming major cost centers for financial institutions.30

- One paper estimates that “[a]n average firm spends 1.34 percent of its total labor costs on performing regulation-related tasks.”31

Regulations also impose costs on the government, such as the costs associated with promulgating regulation, bringing enforcement actions, and adjudicating cases.32 California Governor Gavin Newsom recently vetoed33 AB 1064, which would have regulated companion chatbots made available to minors.34 A previous version of the bill would have established a Kids Standards Board,35 which would have cost the state “between $7.5 million and $15 million annually.”36 To take another infamous example, consider the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA),37 which, inter alia, requires the federal government to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) prior to “major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment.”38 These EISs have grown to become incredibly burdensome, with a 2014 report from the Government Accountability Office estimating that the average EIS took 1,675 days to complete39 and cost between $250,000 and $2 million.40

It is also worth considering the opportunity costs associated with regulation. Regulation requires firms to divert resources away from their most productive use.41 The opportunity cost of a regulation to a firm is therefore the difference between the return the firm would have earned from its most productive use of resources dedicated to compliance and the return those resources in fact earned.42 While more difficult to observe than compliance costs, opportunity costs may be significantly larger over time due to compounding growth.43 Opportunity costs also include the cost to consumers when regulations prevent a product from reaching the market. For example, a working paper found that the European Union’s (EU’s) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) “induced the exit of about a third of available apps” on the Google Play Store, ultimately reducing consumer surplus in the app market by about a third.44

Finally, regulation can have strategic costs not easily captured in economic terms. A number of commentators worry that overregulation of AI in the US could cause the US to lose its lead in AI research and development to foreign competitors, especially China.45 Of course, China for its part has hardly taken a laissez-faire attitude toward its domestic AI industry.46 Nevertheless, it is reasonable to carefully consider international competitiveness when evaluating domestic regulatory proposals.

To be clear, this paper does not argue that the potentially high costs of regulation are a conclusive argument against any particular regulatory proposal. Regulations often have pro tanto benefits, and such benefits must be weighed against costs to decide whether the regulation is socially beneficial on net.47 Nor is this intended to be a comprehensive survey of regulatory burdens. We are merely restating the banal observation that regulations can come at significant cost to societal goods. Any serious discussion of AI policy must be willing to concede that point and entertain approaches to capturing the benefits of well-designed regulation at lower cost to producers, consumers, and society as a whole.

II. Current Approaches to Managing Compliance Costs in AI Policy

Regulators and policy entrepreneurs often make some efforts to reduce the costs associated with regulation. Traditional regulatory literature often proposes using performance-based regulation, which requires regulated parties to achieve certain results rather than use certain methods or technologies, on the logic that performance-based standards allow the regulatees to find and adopt more efficient methods of achieving compliance.48 Tort-based approaches to AI policy49 similarly incentivize firms to identify and implement the most effective means for reducing actionable harms from their systems.50

Nevertheless, there remains substantial interest in prescriptive regulation for AI.51 To date, the most carefully designed proregulatory proposals have tended to use some method for regulatory targeting to attempt to limit regulatory costs to only those firms that are both (a) engaging in the riskiest behaviors and (b) best able to bear compliance costs. Early proposals tended to rely on compute thresholds, wherein only AI models that were trained using more than a certain number of computational operations would be regulated.52 A number of proposed and enacted laws and regulations have used compute thresholds for this reason:

- The EU AI Act states that “A general-purpose AI model shall be presumed to have high impact capabilities . . . when the cumulative amount of computation used for its training measured in floating point operations is greater than 1025.”53

- Regulations proposed under the Biden administration would have required AI companies to report the development of “dual-use foundation models,” which were in turn defined as models that “utilize[] more than 1026 computational operations (e.g., integer or floating-point operations).”54

- The much-debated—and ultimately vetoed55—California SB 104756 would have initially57 applied to models that were “trained using a quantity of computing power greater than 1026 integer or floating-point operations, the cost of which exceeds one hundred million dollars . . . .”58

- California’s recently enacted SB 5359—a successor to SB 1047 focused on transparency—defines “frontier model” as “a foundation model that was trained using a quantity of computing power greater than 1026 integer or floating-point operations.”60

Compute-based thresholds are a reasonable proxy for the financial and operational resources needed to comply with regulation because compute (in the amounts typically proposed) is expensive: when proposed in 2023, the 1026 operations threshold corresponded to roughly $100 million in model training costs.61 Any firm using such amounts of compute will necessarily be well-capitalized. Training compute is also reasonably predictive of model performance,62 so compute thresholds target only the most capable models reasonably well.63 Of course, improvements in compute price-performance64 will steadily erode the cost needed to reach any given compute threshold. This is why some proposals, like SB 1047’s, use a conjunctive test, wherein regulation is only triggered if the cost to develop a covered model surpasses both an operations-based and a dollar-based threshold.

However, newer AI paradigms, such as reasoning models, have complicated the relationship between training compute and AI capabilities.65 Thus, more recent proposals have also argued for regulatory targeting based not on training compute, but rather on some entity-based threshold, as measured by the total amount an AI company spends on AI research or compute (including both training and inference compute).66

III. Automated Compliance

This paper does not suggest abandoning existing approaches to managing regulatory costs in AI policy. It does, however, suggest that such approaches are insufficiently ambitious in the era of AI. In particular, we think that existing approaches often ignore the extent to which AI technologies themselves could reduce regulatory costs by largely automating compliance tasks.67

Compliance professionals already report significant benefits from the use of AI tools in their work,68 and there is no shortage of companies claiming to be able to automate core compliance tasks.69 Such claims must of course be treated with appropriate skepticism, coming, as they do, from companies trying to attract customers. Nevertheless, the large amount of interest in existing compliance-automating AI suggests some reason for optimism.

The most significant promise for compliance automation, however, comes from future AI systems. AI companies are developing agentic AI systems: AI systems that can competently perform an increasingly broad range of computer-based tasks.70 If these companies succeed, then AI systems will be able to autonomously perform an increasingly broad range of computer-based compliance tasks71—possibly more quickly, reliably, and cheaply than human compliance professionals.72 We can call this general hypothesis—that future AI systems will be able to automate many core compliance tasks—automated compliance.

Automated compliance has significant implications for the proregulatory–deregulatory debate within AI policy.73 Before exploring the implications of automated compliance, however, we should be clear about its content. Not all compliance tasks are equally automatable. Unfortunately, we cannot here provide a comprehensive account of which compliance tasks are most automatable.74 However, we can provide some initial, tentative thoughts on which compliance tasks might be more or less automatable.

To start, recall that we limited our definition of “agentic AI” to “AI systems that can competently perform an increasingly broad range of computer-based tasks.”75 Thus, by definition, agentic AI would only be able to automate computer-based compliance tasks; those requiring physical interactions would remain non-automatable.76 An AI agent, under our definition, would not be able to, for example, provide physical security to a sensitive data center.77 Fortunately, many compliance tasks required by AI policy proposals would be computer-based; hence, this definitional constraint does not itself significantly limit the implications of automated compliance for AI policy. Consider the following processes that plausible AI safety and security policies might require:

- Automated red-teaming, in which AI models themselves attempt to “find flaws and vulnerabilities” in another AI system.78 Some frontier AI developers already use automated red-teaming as part of their safety workflows.79

- Cybersecurity measures to prevent unauthorized access to frontier model weights.80 While cybersecurity has some inherently physical components (e.g., limitations on the types of hardware used, key personnel protection),81 many components of strong cybersecurity should be highly automatable in principle.82

- Implementation of some AI alignment techniques. Some AI alignment techniques, such as reinforcement learning from human feedback,83 require significant human input. However, more recent techniques, such as constitutional AI,84 leverage AI feedback. Research into scalable forms of AI alignment, in which AI systems themselves are charged with aligning next-generation AI systems, is ongoing.85

- Automated evaluations of AI systems on safety-relevant benchmarks.86

- Automated interpretability,87 in which AI systems help us understand how other AI models make decisions, in human-comprehensible terms.88

Importantly, automated compliance extends beyond computer science tasks. Advanced AI agents could also help reduce compliance costs by, for example:

- Keeping abreast of updates in the regulatory and legal landscape.89

- Translating regulatory requirements into concrete changes to internal procedure.90

- Filing mandated transparency reports.91

- Designing and delivering employee training.92

- Corresponding with regulators.93

However, not all computer-based compliance tasks would be made much cheaper by AI agents.94 Some compliance tasks might require human input of some sort, which by its nature would not be automatable.95 For example, some forms of red-teaming “involve[] humans actively crafting prompts and interacting with AI models or systems to simulate adversarial scenarios, identify new risk areas, and assess outputs.”96 Automation may also be unable to reduce compliance costs associated with tasks that have an explicit time requirement. For example, suppose that a new regulation requires frontier AI developers to implement a six-month “adaptation buffer” during which they are not permitted to distribute the weights of their most advanced models.97 The costs associated with this calendar-time requirement could not be automated away. Nevertheless, there will be some compliance tasks that will be, to some significant degree, automatable by advanced AI agents.98

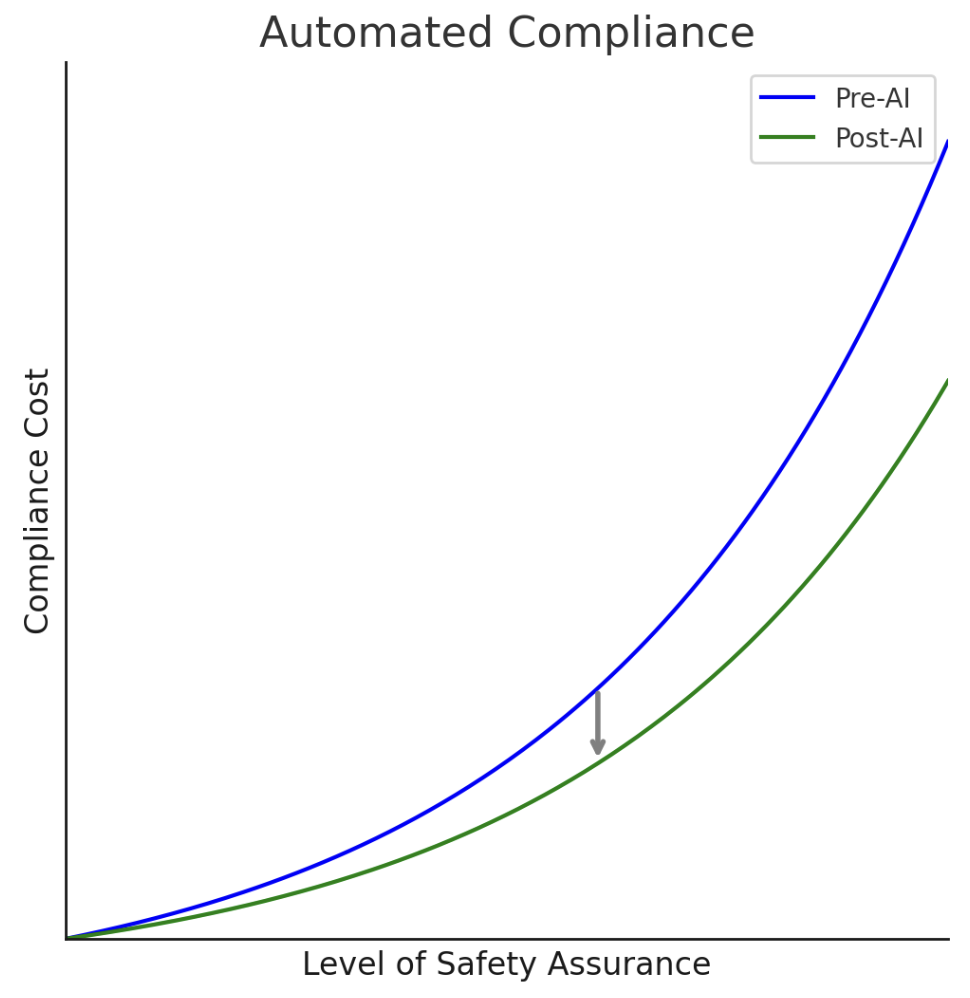

To summarize, as AI capabilities progress, AI systems will themselves be able to perform an increasing fraction of compliance-related tasks.99 The simplest implication of automated compliance is that, holding regulation levels constant, compliance costs should decline relative to the pre-AI era.100 This is hardly a novel observation given the large number of both legacy firms and startups that are already integrating frontier AI technologies into their legal and compliance workflows.101 However, we think that automated compliance has even more significant implications for the design of optimal AI policy. We turn to those implications in the next section.

Figure 1: Automated Compliance illustrated. AI causes the cost to achieve any given level of safety assurance to decline.

IV. Implications of Automated Compliance for Policy Design

A. Automated Compliance and the Optimal Timing of Regulation

Automated compliance can reduce compliance costs associated with some forms of regulation. However, this is only true insofar as the AI technology necessary to automate compliance arrives before (or at least, simultaneously with) the regulatory requirements to be automated.

Thus, even those who agree with our prediction might still worry that automated compliance might become an excuse to implement costly regulation prematurely, in the expectation that technological progress will eventually reduce compliance costs. To be sure, such projections are often reasonable. For example, compliance costs for the Obama Administration’s Clean Power Plan102 were significantly lower than initially estimated due in large part to “[o]ngoing declines in the costs of renewable energy.”103 Nevertheless, when there are genuine concerns about the downsides of premature AI regulation, or simply outstanding uncertainties over the pace or cadence of further progress in compliance-automating AI applications, merely hoping that compliance automation technologies will eventually reduce excessive compliance costs imposed today may seem like a risky proposition.

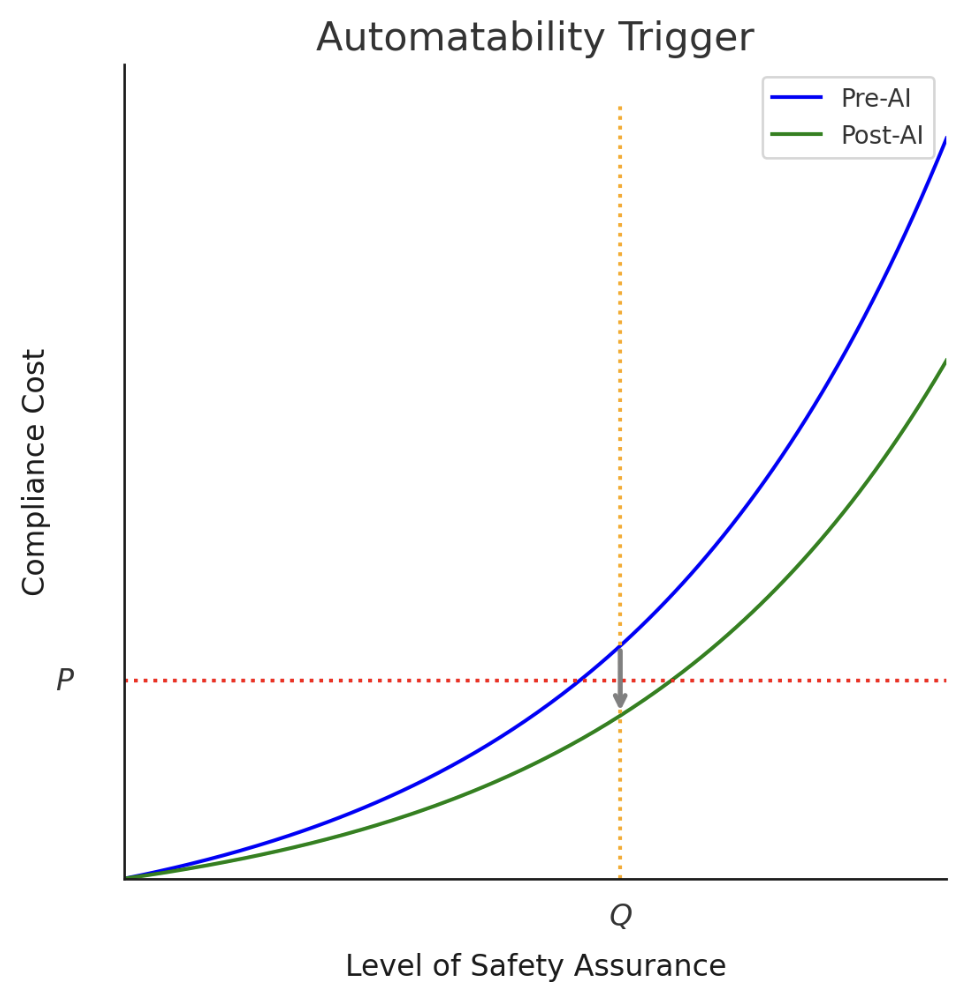

This sequencing problem suggests a natural solution: certain AI safety policies could only be triggered when AI technology has progressed to the point where compliance with such policies is largely automatable. We could call such legal mechanisms automatability triggers.

Developing statutory language for automatability triggers must be left for future work, partly because such triggers need tailoring to their broader regulatory context. However, an illustrative example may help build intuition and catalyze further refinements. Consider a bill that would impose a fine on any person who, without authorization, exports104 the weights of a neural network if such neural network:

(a) was trained with an amount of compute exceeding [$10 million] at fair market rates,105 and

(b) can, if used by a person without advanced training in synthetic biology, either:

(i) reliably increase the probability of such person successfully engineering a pathogen by [50%], or

(ii) reduce the cost thereof by [50%],

in each case as evaluated against the baseline of such a person without access to such models but with access to the internet.106

Present methods for assessing whether frontier AI models are capable of such “uplift” rely heavily on manual evaluations by human experts.107 This is exactly the type of evaluation method that could be manageable for a large firm but prohibitive for a smaller firm. And although $10 million is a lot of money for individuals, it seems plausible that there will be many firms that would spend that much on compute but for whom this type of regulatory requirement could be quite costly. Under our proposed approach, the legislature might consider an automatability trigger like the following:

The requirements of this Act will only come into effect [one month] after the date when the [Secretary of Commerce], in their reasonable discretion, determines that there exists an automated system that:

(a) can determine whether a neural network is covered by this Act;

(b) when determining whether a neural network is covered by this Act, has a false positive rate not exceeding [1%] and false negative rate not exceeding [1%];

(c) is generally available to all firms subject to this Act on fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory terms, with a price per model evaluation not exceeding [$10,000]; and,

(d) produces an easily interpretable summary of its analysis for additional human review.

This sample language is intended to introduce one way to incorporate an automatability trigger into law, and various considerations may justify alternative implementations or additional provisions. For example, concerns about disproportionate compliance costs being borne by smaller labs might justify a subsidy for the use of the tool. Similarly, lawmakers would need to consider whether to make the use of such a tool mandatory. Though it seems likely that most firms would prefer to adopt state-approved automated compliance tools, some may insist on doing things the “old-fashioned way.” Whether that option should be available to firms will likely depend on the extent to which alternative systems would frustrate the ability of the regulator to easily assess compliance. While surely imperfect in many ways, an automatability trigger like this could probably allay many concerns about the regulatory burdens associated with our hypothetical bill.108

Automatability triggers could improve AI policy through two related mechanisms. First, of course, they reduce compliance costs throughout the entire time that a regulation is in force. But more importantly, they also aim to reduce the possibility of premature regulation: they allow AI progress to happen, unimpeded by regulation, until such time as compliance with such regulation would be much less burdensome than at present. Of course, the reverse is also true: automatability triggers might also increase the probability that AI regulations are implemented too late if the risk-producing AI capabilities arrive earlier than compliance-automating capabilities. Thus, the desirability of automatability triggers depends sensitively on policymakers’ preferences over regulating too soon or too late.

Automatability triggers also have key benefits over the primary approaches to controlling compliance costs within AI policy proposals: compute thresholds and monetary thresholds.109 Existing approaches tend not to (directly)110 control absolute costs of compliance, but rather tend to ensure that compliance costs are only borne by well-capitalized firms. Automatability triggers, by contrast, aim to cap compliance costs for all regulated firms.

The prospective enactment of automatability triggers in regulations also sends a useful signal to AI developers: it makes clear that there will be a market for compliance-automating AI and therefore incentivizes development towards that end. This, in turn, implies that trade-offs between safety regulation and compliance costs would loosen much more quickly than by default.

Finally, regulations that incorporate automatability triggers may prove far more adaptable and flexible than traditional, static regulatory approaches—a quality that most experts regard as essential for effective AI governance.111 Traditional rules often struggle to keep pace with rapid technological change, requiring lengthy amendment processes whenever new risks or practices emerge. By contrast, automatability triggers allow regulations to evolve in step with the development of compliance technologies. As automated compliance tools become more sophisticated, legislators and regulators could use them to focus on the precise types of information from labs that are most relevant to the regulatory issue at hand, rather than demanding broad, costly disclosures. This targeted approach not only reduces unnecessary burdens on regulated entities but also increases the likelihood that regulators receive timely, actionable data. Importantly, amendments to laws designed with automatability triggers would not require firms to reinvent their compliance systems from the ground up. Instead, updates would simply involve ensuring that the relevant information is transmitted through the approved compliance tools—making the regulatory framework more resilient, responsive, and sustainable over time.

Although the idea of automatability triggers is straightforward, their design might not be. Policymakers would need to be able to define and measure the cost-reducing potential of AI technologies. This seems difficult to do even in isolation; ensuring that such measures accurately predict the cost-savings realizable by regulated firms seems more difficult still.

Figure 2: Automatability Triggers illustrated. A regulation that provides safety assurance level Q is implemented with an automatability trigger at P: the regulation is only effective when the cost to implement the regulation falls below P. Regulated parties are thus guaranteed to always have compliance costs below P.

B. Adoption of Compliance-Automating AI as Evidence of Compliance

Automatability triggers assume that regulators can competently identify AI services that, if properly adopted, enable regulated firms to comply with regulations at an acceptable cost. If so, then we might also consider a legal rule that says that regulated firms that properly implement such “approved” compliance-automating AI systems are presumptively (but rebuttably) entitled to some sort of preferential treatment in regulatory enforcement actions. For example, such firms might be inspected less frequently or less invasively than firms that have not implemented approved compliance-automating AI systems. Or, in enforcement actions, they might be entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they were in compliance with regulations while using such systems.112 Or a statute might provide that proper adoption of such a system is conclusive evidence that the firm was exercising reasonable care so as to preclude negligence suits.

Of course, it is important that such safe harbors be carefully designed. They should only be available to firms that were properly implementing compliance-automating AI. This would also mean denying protection to firms who, for example, provided incomplete or misleading information to the compliance-automating AI or knowingly manipulated it, causing it to falsely deem the firm to be compliant. Compliance-automating AIs, in turn, should ideally be robust to such attempts at manipulation. Regulators would also need to be confident that, if properly implemented, compliance-automating AI systems really would achieve the desired safety results in deployment settings. Finally, in the ideal case, regulators would ensure that the market for compliance-automating AI services is competitive; reliance on a small number of vendors who can set supracompetitive prices would reduce the cost-saving potential of compliance-automating AI and concentrate its benefits among the firms with deeper pockets. For example, perhaps regulators could accomplish this by only implementing such an approval regime if there were multiple compliant vendors.113

C. Differential Acceleration of Automated Compliance

Automated compliance can be analyzed through the lens of “risk-sensitive innovation”: a strategy for deliberately structuring the timing and order of technological advances to “reduce specific risks across a technology portfolio.”114 Targeted acceleration of the development of compliance-automating AI systems could reduce painful trade-offs between safety and innovation in a very fraught and uncertain policy environment. It is therefore worth considering what, if anything, AI policy actors can do to differentially accelerate automated compliance.

Of course, there will be a natural market incentive to develop such technologies: regulated parties will need to comply with regulations and will be willing to pay anyone that can reduce the costs of compliance. Indeed, we have mentioned some examples of how firms are already using AI to reduce compliance costs.115 But prosocial actors may be able to further accelerate automated compliance by, for example:116

- Building curated data sets that would be useful for creating compliance-automating AI systems.117

- Subsidizing compute access for developers attempting to build compliance-automating AI systems.118

- Building proof-of-concept compliance-automating AI systems for existing regulatory regimes.

- Preferentially developing and advocating for AI policy proposals that are likely to be more automatable.

- Educating policymakers on which types of regulations are more likely to be compatible with regulatory compliance.

- Instituting monetary incentives, such as advance market commitments, for compliance-automating AI applications.119

- Ensuring that firms working on automated compliance have early access to restricted AI technologies.120

- Building AI systems that automate key technical AI safety tasks that might be required by AI safety regulation, such as those listed above.121

- Building AI systems that automate key non-technical legal and compliance tasks, such as those listed above.122

D. Automated Compliance Meets Automated Governance

So far, we have been focusing on the costs and benefits to regulated parties. However, automated compliance might be especially synergistic with automation of core regulatory and administrative processes.123 For example, regulatory AI systems would be well-positioned to know how proposed regulations would affect regulated companies and could therefore be used to write responses to proposed rules.124 Regulatory AI systems, in turn, could compile and analyze these comments.125 Indeed, AI systems might be able to draft and analyze many more variations of rules than human-staffed bureaucracies could,126 thus enabling regulators to receive and review in-depth, tailored responses to many possible policies and select among them more easily.

Compliance-automating AI systems could also request guidance from regulatory AI systems, who could review and respond to the request nearly instantaneously.127 Such guidance-providing regulatory AI systems could be engineered to ensure that business information disclosed by the requesting party was stored securely and never read by human regulators (unless, perhaps, such materials became relevant to a subsequent dispute), thus reducing the risk that the disclosed information is subsequently used to the detriment of the regulated party.

Of course, there are many governance tasks that should remain exclusively human, and automating core governance tasks carries its own risks.128 But future AI systems could offer significant benefits to both regulators and regulatees alike, and may be even more beneficial still when allowed to interact with each other according to predetermined rules designed to mitigate the potential for abuse by either party.

Conclusion

AI systems are capable of automating an increasingly broad range of tasks. Many regulatory compliance tasks will be similarly automatable. This insight has important implications for the ongoing debate about whether and how to regulate AI. On the one hand, forecasts of regulatory compliance costs will be overstated if they fail to account for this fact; AI progress itself hedges the costs of many forms of AI regulation. Regulatory design should account for this dynamic. However, to maximize the benefits of automated compliance, regulators must successfully navigate a tricky sequencing problem. If regulations are triggered too soon—that is, before compliance costs have fallen sufficiently—they will hinder desirable forms of AI progress. On the other hand, if they are triggered too late—that is, after the risks from AI would justify the regulations—then the public may be exposed to excessive risks from AI. Smart AI policy must be attentive to these dynamics.

To be clear, our claim is fairly modest: AI progress will reduce compliance costs in some cases. Automated compliance is only relevant when compliance tasks are in fact automatable, and not all compliance tasks will be. Accordingly, the costs of some forms of AI regulation might remain high, even if many compliance tasks are automated. And of course, regulations are only justified when their expected benefits outweigh their expected costs. Furthermore, regulations have costs in excess of their directly measurable compliance costs;129 these costs are no less real than are compliance costs. The availability of compliance-automating AI should not be used as an excuse to jettison careful analysis of the costs and benefits of regulation. Nevertheless, AI policy discourse should internalize the fact that AI progress implies reduced compliance costs, all else equal, due to automated compliance.