Mapping AI Policy: Where, Why, and How to Intervene

Abstract

State lawmakers introduced over 1200 bills on artificial intelligence (AI) in 2025, nearly doubling the number from the year before. Almost 150 were enacted.[ref 1] They cover topics as varied as deepfakes, biased decision-making systems, or rogue AI systems. Yet the media describes them all as “AI legislation,” revealing an impreciseness that makes it hard for legal practitioners, policymakers, and the public to understand key AI policy issues.

This primer offers a framework for thinking more precisely about AI policy. It analyzes legislation along three dimensions: the harm being addressed (the why), the factors that should guide intervention design (the how), and the actor in the AI ecosystem being targeted (the where).

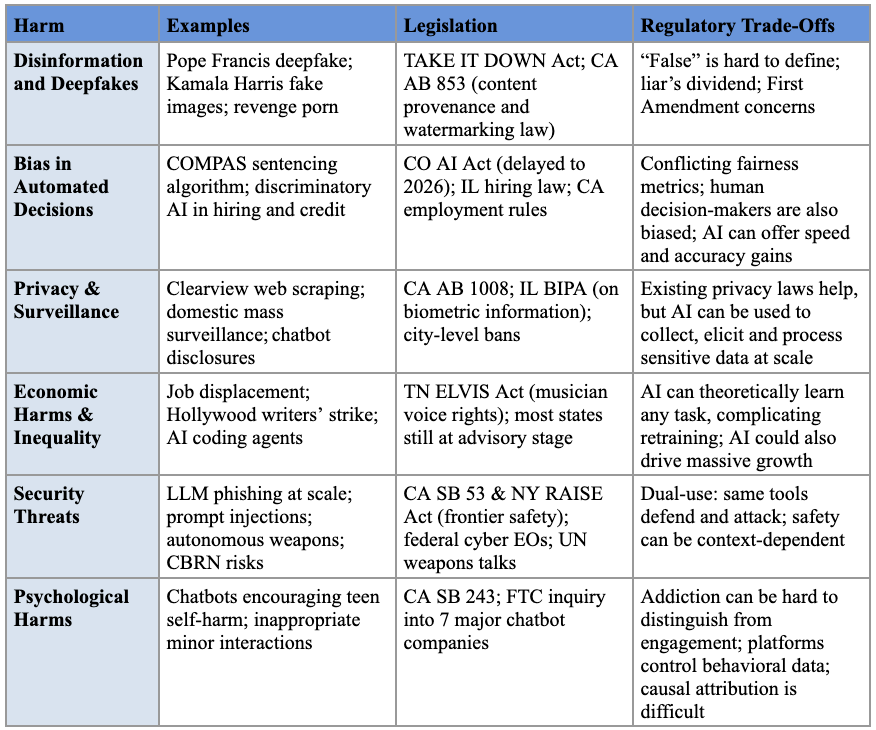

Part I organizes the universe of AI harms into six categories: (1) mis- and disinformation-related harms; (2) bias in automated decision systems; (3) privacy and surveillance harms; (4) economic harms and inequality from automation; (5) security threats; and (6) psychological harms. With so many applications being called AI—including search engines, chatbots, pricing algorithms, and robots—lawmakers risk being overwhelmed by the consequences of AI if they do not have a clear goal in mind.

Part II introduces seven design factors that recur across harms and stages: whether to prevent harms or respond to them, how an intervention affects concentration of power, whether regulation is the right tool at all, and others. These factors are often in tension. An intervention that decentralizes the AI ecosystem may make enforcement harder; one that restricts offensive capabilities may also degrade beneficial ones.

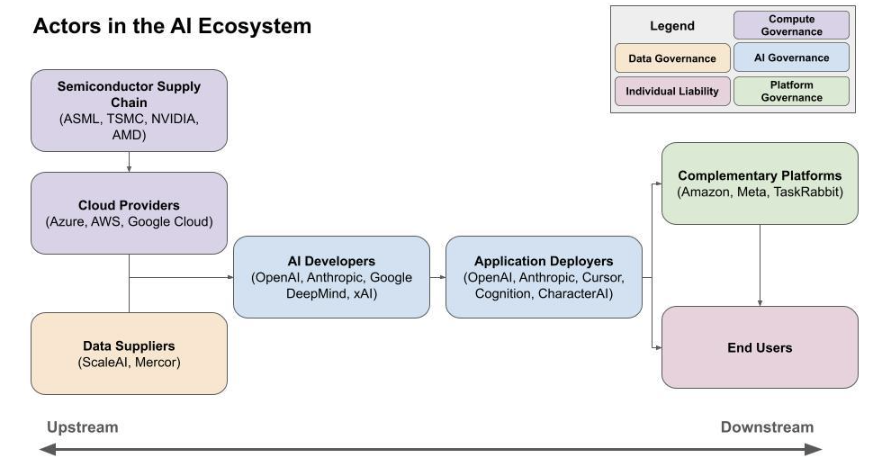

Part III maps the actors in the AI ecosystem—from chip manufacturers to end users—and analyzes the advantages and limitations of targeting each. Analyzing AI in this way highlights the distinct functions performed by the actors within the AI ecosystem, enabling policymakers to design more tailored interventions rather than relying on overly broad regulatory categories.

Ultimately, this primer underscores two core principles for navigating the complexities of AI policy. First, the more precisely policymakers can identify the harm and the actor best positioned to prevent it, the more effective their interventions are likely to be. Second, policymaking in this rapidly evolving domain is rarely simple; there are few free lunches, and choices will inevitably require confronting difficult tradeoffs. Accordingly, this primer does not advocate for specific policy positions. It offers a framework to empower policymakers to make better decisions on AI.

I. The Why: What AI-Related Harm Does the Policy Intervention Address?

To understand how to regulate AI, policymakers must first understand why they want to regulate it. How can one write laws to achieve a desirable end without knowing what that end is? This part gives policymakers language for specifying what they wish to achieve by outlining the AI-related harms they might wish to address.

The categories below are neither mutually exclusive nor comprehensive. One practice, for example, can fit into multiple buckets of harm. Algorithmic pricing, where companies use AI to charge different consumers different prices for the same product, can cause privacy harms (through the surveillance data collection that powers it), economic harms (through the higher prices it can impose), and bias harms (when higher prices correlate with protected characteristics like race or religion).

They are intended to be an illustrative list of commonly referenced AI harms that can serve as a starting point for policymakers writing and debating AI legislation. In particular, this primer does not address environmental harms from AI training and deployment or the intellectual property issues that arise from the use of copyrighted material in AI training. Here our focus is on harms caused by using AI, not those arising from the process of creating AI systems.

Each of the following subsections describes an example of the harm, offers examples of relevant legislation, and explains the unique aspects of the harm that make it difficult to address, as well as benefits that might be lost if the regulations are poorly designed.

A. Misinformation and Disinformation-Related Harms

The potential harms of AI-generated content resurface in the public discourse each time a deepfake goes viral. In 2023, a fabricated image of Pope Francis in a white puffer highlighted the impressive capabilities of state-of-the-art image generators,[ref 2] while the circulation of AI-generated images by Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2024—depicting his rival Kamala Harris at a communist rally and the singer Taylor Swift as a campaign supporter—underscored the technology’s potential for political disruption.[ref 3]

Amidst these concerns, several states have already enacted some legislation, though they have largely focused on two specific contexts: politics and pornography. To protect election integrity, over half of states have enacted laws requiring disclaimers on or banning the distribution of deceptive AI-generated campaign media.[ref 4] In addition, nearly all states have enacted laws prohibiting deepfake non-consensual intimate imagery (“revenge porn”).[ref 5] At the federal level, the recently enacted TAKE IT DOWN Act further strengthens these protections by creating a private right of action against individuals who produce or share such content and by requiring platforms to remove it upon notification.[ref 6]

Beyond these targeted applications, some legislative efforts have aimed to address content authenticity more broadly. California’s AI Transparency Act, for example, requires developers of generative AI models to enable digital watermarking and content provenance capabilities.[ref 7]

Despite this legislative activity, addressing the misinformation-related harms of AI remains challenging for at least four reasons. First, defining “false” or “misleading” in an objective, consistent, and apolitical way is extraordinarily difficult.[ref 8]

Second, the public perception of widespread misinformation is itself dangerous by eroding trust in the information ecosystem, creating a “liar’s dividend” where authentic content is more easily dismissed as fake.[ref 9]

Third, many interventions face First Amendment hurdles because they may infringe upon the free speech rights of platforms or users. This is not a theoretical concern; federal courts have enjoined Hawaii’s and California’s election deepfake laws, reasoning that their broad scope could unconstitutionally chill protected forms of speech like parody and satire.[ref 10]

Fourth, overly stringent regulations could inadvertently cripple the very capabilities that make large language models transformative. If LLM performance substantially suffers from excessive content restrictions, burdensome compliance mandates, or unclear liability rules, their utility could be severely diminished.[ref 11] For instance, models might become overly cautious, refusing to engage with complex or sensitive topics, thereby limiting their effectiveness as educational tools or research assistants.[ref 12]

B. Bias in Automated Decision Systems

Bias—systematic errors that result in unfair outcomes against certain individuals or groups—can enter AI systems through unrepresentative training data, societal prejudices reflected in that data, or the very objectives developers set for an algorithm.[ref 13] The stakes are high, as automated systems now make some of the most consequential decisions in people’s lives. For example, the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) algorithm has been used for years by judges nationwide to generate “risk assessments” for criminal sentencing.[ref 14] Despite concerns around racial, gender, and other biases in tools like COMPAS, such systems are widely used in other critical areas, including hiring[ref 15] and access to credit,[ref 16] among others.

Colorado’s AI Act (SB 24-205) is the signature legislation designed to address this problem.[ref 17] Enacted in May 2024, it requires developers of high-risk systems to use “reasonable care” to protect consumers from algorithmic discrimination by mandating risk management programs and impact assessments. However, because its provisions have been delayed until at least June 2026, the bill’s real-world impact remains to be seen.[ref 18] Other states have followed Colorado’s lead with their own variations: Virginia’s legislature passed a similar bill that was ultimately vetoed,[ref 19] Illinois enacted a law targeting discriminatory AI in hiring,[ref 20] and California has issued anti-discrimination regulations for automated employment systems.[ref 21]

Addressing AI biases has proven difficult, despite nearly a decade of awareness among policymakers and technologists. A core challenge is translating abstract concepts of “fairness” into quantifiable metrics; researchers have identified at least 21 distinct mathematical definitions of fairness,[ref 22] many of which are mutually exclusive.[ref 23] Furthermore, restricting automated systems over bias concerns presents a difficult trade-off. Doing so could mean reverting to human decision-makers, who have their own biases,[ref 24] while also sacrificing the speed, cost-efficiency, and potential accuracy gains that algorithms offer.

C. Privacy and Surveillance Harms

AI creates privacy and surveillance risks at three key stages: when information is collected to build AI, when it is exposed while using AI, and when AI is deployed to collect and process new information.

The first risk arises from the data collection used to train AI models, which often includes personal information scraped from the internet without an individual’s consent. The facial recognition company Clearview AI, for example, built its database by scraping billions of images from platforms like Facebook.[ref 25] This practice has prompted legal challenges, such as a lawsuit alleging that Clearview’s data scraping violated Illinois’s Biometric Information Privacy Act along with privacy laws in several other states, which resulted in a $50 million settlement.[ref 26]

A second privacy risk emerges when users share intimate details with interactive systems like AI chatbots.[ref 27] States are beginning to adapt their privacy laws for this new reality. California’s Assembly Bill 1008, for instance, amends the state’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) to clarify that personal information output by AI systems is covered by existing privacy protections.[ref 28]

Finally, AI serves as a powerful tool for surveillance. For example, by 2023 U.S. police had performed nearly a million facial recognition searches using Clearview AI.[ref 29] In response, several states have enacted limitations on police use of facial recognition. Massachusetts is one of the few states to restrict police use of the technology,[ref 30] while some cities have banned its use by government agencies altogether.[ref 31] The Pentagon-Anthropic dispute was a recent flashpoint around this exact issue.[ref 32]

Regulating AI’s privacy harms presents a paradox. On one hand, the issue may be more tractable than other AI risks because states have spent years developing legal frameworks for data privacy that can be adapted to AI. On the other hand, regulation is uniquely difficult because many of AI’s transformative benefits are tied to its ability to process massive amounts of sensitive data. This creates complex trade-offs, such as balancing the public safety benefits of AI surveillance against individual privacy rights.

D. Economic Harms and Inequality From Automation

The fear that AI will automate jobs, further concentrating wealth and power in the hands of a few private actors, looms over many discussions about the technology.[ref 33] These fears are so significant that Hollywood writers went on strike over the potential threat to their livelihoods,[ref 34] while many illustrators worry about the future of their profession[ref 35] due to advanced image generators like Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and Gemini and ChatGPT’s image generation features.

Tennessee’s ELVIS Act, which extended an artist’s publicity rights to include AI-generated voice content, is an early attempt at addressing the economic effects of AI and narrowly focuses on entertainment industries.[ref 36] More comprehensive legislation seems unlikely in the near future, particularly as many states have only recently convened AI advisory groups to research and plan for future economic changes.

Lawmakers will likely continue to struggle with mitigating these impacts due to the unpredictability of AI’s future capabilities. Thus far, advancements have been both rapid and uneven.[ref 37] For example, OpenAI’s o1 model marked a sudden and significant leap in large language models’ ability to solve mathematical problems[ref 38]—an area where previous models were heavily criticized for underperformance.[ref 39] More recently, AI coding agents like Claude Code have progressed from autocomplete assistants to autonomous systems capable of writing code with minimal human oversight, disrupting a profession many once assumed was insulated from automation.[ref 40] With AI capabilities advancing this quickly and unpredictably, it becomes increasingly difficult for policymakers to identify which professions are most at risk of automation, let alone determine the appropriate timeline for addressing these challenges.

Yet the potential economic benefits are also massive. In some ways, the worst-case scenario might also be the best-case. The more jobs that are automated by AI, the more powerful the AI system. If these systems do become the functional equivalent of a “country of geniuses in a datacenter,” the economic growth and quality of life improvements can be substantial.[ref 41] And if such benefits can be distributed equitably (an admittedly big if), the economic future enabled by AI can be far better than what exists today.

E. Security Threats

The spectrum of AI-related security threats is broad, ranging from digital vulnerabilities that compromise data and systems to physical dangers that threaten lives and infrastructure. AI can increase the frequency and scale of these incidents both by amplifying existing risks and by introducing entirely new vulnerabilities.

In the cybersecurity domain, AI can be a force multiplier for malicious actors.[ref 42] Large language models can be used to generate sophisticated spear-phishing emails (targeted attacks disguised as legitimate communication) at an unprecedented scale or to automatically detect vulnerabilities in codebases.[ref 43] Beyond amplifying old threats, AI models themselves introduce new attack vectors when integrated into digital services.[ref 44] For example, “indirect prompt injection” vulnerabilities have allowed attackers to take control of a user’s session in a chatbot and steal their conversation history.[ref 45] As more services incorporate these AI tools, such vulnerabilities create new routes for attackers to compromise systems.

The potential for physical threats is also deeply concerning. State actors can use AI to augment intelligence capabilities, deploy more sophisticated weapons like lethal autonomous weapons (LAWs), and enhance their capacity to conduct cyberattacks against critical infrastructure.[ref 46] Furthermore, AI lowers the barrier for non-state actors to access dangerous capabilities, potentially making it easier to develop and deploy chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) weapons.[ref 47]

Legislative efforts to address these threats have emerged at the state, federal, and international levels. The most prominent state-level proposals have targeted developers of frontier AI models. California’s SB 53[ref 48] and New York’s RAISE Act,[ref 49] signed into law in September and December 2025, respectively, impose largely similar requirements: both require large frontier developers to publish safety frameworks, report critical safety incidents, and face civil penalties for noncompliance. Together, the two laws are beginning to function as a de facto national standard for addressing catastrophic AI risks.

At the federal level, Congress has shown interest in AI’s role in cyberspace,[ref 50] and the Biden administration issued Executive Orders to both accelerate the use of AI in national cyber defense[ref 51] and (in an order since repealed by the Trump administration) to oversee advanced AI development through measures like compute cluster reporting and “Know-Your-Customer” (KYC) requirements for cloud providers.[ref 52] Internationally, forums like the UN Group of Governmental Experts on LAWs have been exploring frameworks to regulate AI in warfare.[ref 53]

Despite these efforts, mitigating security threats remains challenging. A core difficulty is AI’s dual-use nature: the same capabilities that can help people defend and improve systems can also be used to help malicious actors attack them. Organizations are already using AI to detect phishing attempts and patch vulnerabilities, and Microsoft alone blocks tens of billions of threats annually. The difficulty with dual-use is compounded by the fact that safety is not an inherent property of an AI model. Just as an electric motor’s safety depends on its application, an AI model’s potential for harm is context-dependent, making it difficult to assign liability or design proactive, one-size-fits-all regulations. Finally, the sheer technical complexity and vast scale of these systems make designing comprehensive and effective policy interventions an incredibly difficult task.

F. Psychological Harms

Beyond physical, economic, or information-related threats, AI systems have the potential to cause significant psychological harm, particularly among vulnerable populations like children and adolescents.

AI companions and social media algorithms are engineered to maximize engagement through personalized content and simulated empathetic responses, which can lead to excessive use and what some researchers term “addictive intelligence.”[ref 54] Such AI interactions risk supplanting real-world relationships and exacerbating feelings of loneliness and social isolation, even when initially perceived as helpful.[ref 55] Moreover, over-reliance on AI for social connection may impair interpersonal skills, as AI relationships often lack the reciprocity, spontaneity, and nuanced emotional engagement characteristic of human connections.[ref 56]

Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to these risks. Multiple recent lawsuits allege that AI chatbot companies’ products have contributed to teen suicides, self-harm, and other psychological harms. Plaintiffs have alleged that chatbots discouraged users from seeking help from parents or professionals, engaged in inappropriate sexual interactions with minors, and encouraged addictive and unhealthy relationships.[ref 57]

States are beginning to pass legislation targeting these harms.[ref 58] Yet enacting laws to mitigate psychological harms creates several distinct challenges. First, identifying psychological harm is difficult: clinical addiction can be confused for high engagement and vice versa. Second, this definitional challenge is confounded by a measurement problem: the platforms suspected of causing harm often exclusively control the behavioral data (such as time on device) necessary to assess that harm. Third, attributing harm directly to AI proves difficult in a landscape where multiple factors influence mental well-being. Fourth, many interventions—especially those targeting algorithmic design or content—raise significant free speech concerns.[ref 59] Finally, effective regulation must balance these harms against AI’s potential psychological benefits, including improved access to mental health support and personalized therapeutic interventions that might otherwise be unavailable.

* * *

Ultimately, this overview of some of the harms of AI is intended to remind policymakers of the importance of deciding what they want to accomplish before deciding how they want to regulate. An added benefit is that it allows policymakers to better understand AI legislation passed in other states. Consider two high-profile AI bills: Colorado’s AI Act (SB 24-205), which targets bias in automated decision systems, and California’s Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act (SB 53), which addresses catastrophic risks from frontier AI models. Despite their completely different areas of focus, both are described in media as landmark AI legislation. This missing nuance may lead policymakers to incorrectly believe that they need only pass one omnibus “AI” bill when the reality is they will likely need to pass many AI-related bills to address the technology’s multifaceted harms. Once policymakers know why they want to regulate, the next Part helps them understand how.

II. The How: What Factors Shape Intervention Design?

This part introduces seven factors that should guide policymakers in thinking about where and how to intervene to mitigate AI harms. These factors are not mutually exclusive. A single intervention will implicate multiple principles in ways that might be in tension with each other, which is part of why AI regulation is so difficult. For example, an intervention that encourages the proliferation of open-weight models could mitigate concerns about undue concentration of power (factor 3), while making it harder to limit the offensive capabilities of malicious actors (factor 2) and enforce regulations (factor 5).

A. Harm Prevention (Ex Ante) vs. Harm Response (Ex Post)

Interventions can be distinguished by whether they aim to prevent harms before they occur (ex ante) or respond to harms after they materialize (ex post).[ref 60] Licensing regimes,[ref 61] pre-deployment testing requirements,[ref 62] capability restrictions,[ref 63] and deterrence strategies[ref 64] are more preventive. Incident reporting[ref 65] and content takedown obligations[ref 66] are more responsive. Tort liability has elements of both: it’s responsive in that it awards compensation to harmed parties, but it’s also preventative in that the threat of future sanctions incentivizes companies to prevent those harms in the present. [ref 67]

Whether preventative or responsive interventions are preferable will often depend on the nature of the harm.[ref 68] Preventive interventions are more valuable when harms are difficult or impossible to reverse, such as election interference that cannot be “un-voted”[ref 69] or physical harms that cannot be undone.[ref 70] But preventive interventions require predicting harms in advance and risk being overbroad, which can be difficult for general-purpose technologies like AI that have so many applications. Responsive interventions allow society to learn from harms and calibrate policy accordingly,[ref 71] but they provide cold comfort to those who are harmed as the legal system learns to adapt. An effective regulatory regime will likely need some combination of both.

The speed of harms also bears on the choice between harm prevention and response. Some AI harms materialize rapidly, such as a cybersecurity attack on critical infrastructure or a viral deepfake in the final days of an election, leaving little time to respond. Others occur more slowly: erosion of trust in information or the long-term impacts of a biased AI loans system. For fast-moving harms, ex ante intervention may be essential if ex post remedies arrive too late to matter.

Distributional considerations further complicate the comparison. Ex ante compliance costs are initially borne by developers and typically passed on to consumers. Ex post costs fall first on victims, who must bear the harm and then seek compensation through legal processes that may be slow, expensive, and uncertain. This asymmetry matters especially when AI systems harm people poorly equipped to navigate ex post remedies: individuals without resources to hire lawyers or diffuse groups suffering harms too small individually to justify litigation but significant in aggregate. A regime that relies heavily on ex post liability may systematically undercompensate these populations, even if it works well for well-resourced plaintiffs with clear injuries.

B. Strengthening Defense (Armor the Sheep) vs. Weakening Offense (Defang the Wolves)

Interventions can also be categorized by whether they primarily aim to restrict offensive capabilities (making it harder for bad actors to cause harm) or enhance defensive capabilities (making potential targets more resilient to attack).[ref 72] Export controls and licensing regimes are examples of offensive restriction; they attempt to keep dangerous capabilities out of the “wrong” hands. Investments in cybersecurity infrastructure and early-warning systems are examples of defensive enhancement;[ref 73] they assume adversaries will obtain offensive capabilities and focus on defending against harm.

For some harms, reducing offensive capabilities may be the only viable mechanism. We don’t have defensive approaches to handling the harms created by nuclear weapons, so reducing offensive capabilities through nonproliferation treaties and deterrence strategies is the only viable approach. But offense-reduction strategies are often a double-edged sword: they create incentives for targets to develop workarounds,[ref 74] require centralizing power for enforcement,[ref 75] and can degrade AI’s beneficial capabilities. Because restricting offensive capabilities is difficult[ref 76] and can have undesirable consequences,[ref 77] we recommend that policymakers adopt defense-enhancing strategies for AI where possible.

Defense-enhancing strategies can be both regulatory and technological. Whistleblower protections[ref 78] and incident reporting help companies and regulators identify and respond to harms more quickly.[ref 79] These are legal choices that can improve a jurisdiction’s “resilience” to harms. Vitalik Buterin popularized the technological equivalent with a theory he calls defensive accelerationism (“d/acc”),[ref 80] analogizing to “armoring the sheep” rather than trying to “defang the wolves.”[ref 81] The d/acc movement aims to accelerate the development of defensive technologies. For biosecurity, this might look like installing better HVAC systems or accelerating vaccine development for AI-enabled bioweapons or pandemics. For cybersecurity, this might look like using AI systems like Claude Code or Devin to automatically identify and patch security vulnerabilities.[ref 82] Bernardi et al.’s “Societal Adaptation to Advanced AI” is an excellent primer for thinking about what these defensive strategies might look like.[ref 83]

C. Impact on Concentration of Power

The AI policy community is divided over whether harm mitigation is better served by centralizing or decentralizing the AI ecosystem.[ref 84] This consideration typically runs together with the previous one (ex ante vs ex post harm prevention)[ref 85] because reducing offensive capabilities (model nonproliferation, export controls, etc.) often requires centralizing power for effective enforcement.[ref 86]

The choice between centralization and decentralization is not binary and the considerations differ across layers of the AI stack (see below). At the infrastructure layers (semiconductor supply chain, cloud compute providers), a concentrated chip supply chain can simultaneously create chokepoints useful for export controls and supply-chain vulnerabilities.[ref 87] At the application layer, decentralization enables AI applications tailored to a wide range of specific contexts, though it may complicate efforts to enforce regulations.[ref 88] Policymakers should consider how a given intervention affects concentration at each layer, recognizing that the arguments will vary depending on the layer.

A decentralized ecosystem can improve safety through redundancy and distributed detection of problems. If one developer’s system fails or exhibits unexpected behavior, others may catch the issue.[ref 89] Decentralization also reduces the stakes of any single failure; an error by one of many competitors is likely to be less catastrophic than an error by a dominant player. Yet decentralization can also undermine safety by creating races to the bottom, where competitive pressure leads developers to cut corners on safety investments that don’t translate into market advantage.[ref 90] Fragmented oversight becomes harder when regulators must monitor dozens of developers, and coordination on shared safety standards grows more difficult as the number of actors multiplies.

Concentration also implicates separate questions about industrial policy. Tim Wu has argued that highly concentrated industries develop outsized lobbying power and capture regulators.[ref 91] On this view, the concern is not merely that a few AI developers might build unsafe systems, but that they might accrue sufficient political influence to weaken the oversight meant to constrain them.[ref 92] At the same time, concentration intersects with industrial policy objectives and anxieties about geopolitical competition. Policymakers who worry about competition with China may favor cultivating “national champions:” a small number of well-resourced domestic firms capable of matching foreign competitors.[ref 93]

Each of the interventions discussed in this primer can be located on a spectrum from promoting centralization to decentralization, and policymakers should consider not only which end of that spectrum aligns with their beliefs about AI risk, but also how concentration at different layers of the stack interacts with the offense-defense balance and enforcement.

D. More Upstream Interventions are More Blunt

The amount of context needed to identify a harm will influence where in the ecosystem (see below) to intervene. Upstream interventions (Stages 1–3) are often better suited for context-independent harms because they can restrict capabilities without needing to evaluate specific uses.[ref 94] Downstream interventions (Stages 4–6) are often better able to address context-dependent harms because deployers and users have more information about how AI is actually being used.[ref 95]

Truly context-independent harms are rare since many AI capabilities are dual-use. The same capacity that generates phishing emails also drafts legitimate marketing copy. The same image capability that can produce nonconsensual intimate imagery creates art. Even capabilities that seem clearly dangerous often sit on a spectrum: a model’s ability to discuss virology in detail could facilitate bioweapon development or accelerate vaccine research depending on who is using it and why.[ref 96] But it’s still a useful principle. Some harms are identifiable without knowing much about the circumstances in which AI is used. The production of child sexual abuse material, for instance, is harmful regardless of context. Other harms depend heavily on context: whether a piece of AI-generated content constitutes misinformation, satire, or parody depends on how it is distributed and received.

Downstream interventions can be more precisely targeted, restricting specific uses while leaving others untouched.[ref 97] A platform can prohibit using its AI tools for generating political advertisements without restricting political speech more broadly. A deployer can implement know-your-customer requirements that screen out bad actors while permitting legitimate users. But this precision comes at a cost: downstream interventions often require the capacity to monitor and evaluate specific uses, which may be practically difficult at scale, may require centralization (see above), and shift enforcement burdens to actors who may lack the resources or incentives to implement them effectively.[ref 98]

E. Enforcement Feasibility (Certainty vs. Severity of Penalties)

Traditional enforcement through the legal system requires identifiable defendants within a jurisdiction who can be compelled to pay damages or serve sentences.[ref 99] When these conditions are met, interventions targeting applications and users can be highly effective because they address harms where they occur.

But many AI-related harms involve actors who are difficult or impossible to reach through traditional enforcement: foreign adversaries, anonymous bad actors, autonomous AI systems, or diffuse harms for which no single defendant is responsible. In these situations, compute governance (Stages 1–2) becomes more valuable because it operates through chokepoints—concentrated infrastructure that can be controlled even when end users cannot be.[ref 100]

Policymakers assessing enforcement feasibility should consider three questions. First, can compliance be observed?[ref 101] Some requirements are relatively easy to verify (e.g., whether a model has been submitted for pre-deployment review, whether a chip shipment crossed a border). Others are harder to monitor (e.g., whether a company’s internal safety practices match its public commitments). When compliance is difficult to observe, enforcement depends on whistleblowers, audits, or investigations, which are more resource-intensive yet less complete.[ref 102]

Second, who will enforce? Regulatory requirements need an agency with the statutory authority, technical expertise, and budget to monitor compliance and pursue violators.[ref 103] If that agency doesn’t exist or is underfunded, requirements may go unenforced.

Third, what are the consequences for non-compliance, and are they sufficient to deter? A small fine may be treated as a cost of doing business; a large fine may deter only if the probability of detection is meaningful. An important note is that the certainty of apprehension and punishment matters far more than the severity of punishment for deterrence.[ref 104] For AI governance, this implies that investing in monitoring and detection infrastructure may be more valuable than increasing statutory penalties.[ref 105] It also suggests that highly publicized enforcement actions, which increase the perceived certainty of consequences, may matter more than their direct effects on the individual defendants involved.

Market structure also shapes which tools are feasible. When an industry is concentrated, regulation is more tractable: fewer entities to monitor, greater compliance capacity, and reputational stakes that give enforcement actions bite.[ref 106] When an industry is fragmented, direct regulation may be impractical, pushing policymakers toward upstream chokepoints or tools like liability that don’t require entity-by-entity oversight. When entry barriers are low, regulations binding only incumbents may simply shift activity to less scrupulous providers.

F. Allocating Responsibility to the Least-Cost Avoider

A foundational principle of tort law holds that liability for a harm should be assigned to the party who can most cheaply and effectively prevent it: the “least-cost avoider.”[ref 107] This principle provides useful guidance for allocating responsibility across the AI ecosystem.[ref 108]

In practice, identifying the least-cost avoider is contested. Consider an AI system that generates plausible-sounding medical misinformation that a user then relies upon.[ref 109] Is the least-cost avoider the developer (who could have trained the model to be more cautious about medical claims), the deployer (who could have added guardrails or warnings), the platform that distributed the content (who could have labeled or filtered it), or the user who relied on it without verification? Each could have prevented the harm at some cost, and reasonable people will disagree about which intervention was cheapest or most effective (not to mention the contested normative question of who “ought” to have prevented the wrong).

The principle nevertheless provides a useful starting point: for harms resulting from unpredictable system failures (such as hallucinations), developers and deployers may be best positioned to invest in prevention because they are best positioned to build the scaffolding necessary to protect an AI system. For harms resulting from intentional misuse by end users, this principle may suggest focusing on the end user because they choose whether and how to deploy AI for harmful purposes.[ref 110] For harms that are harmful regardless of context (like CSAM generation), joint and several liability across the production chain may be appropriate to ensure all parties have incentives to prevent it.[ref 111]

G. Is Regulation the Right Tool?

Finally, policymakers should ask whether regulation is the right intervention at all. It is one tool among many, and depending on the type of harm, other interventions may be more effective.

Consider the range of alternatives. Investing in and adopting defensive technologies (like the kind described in subsection 2), for example, may be more effective in reducing cybersecurity vulnerabilities than regulation mandating cybersecurity best practices. Technical standards development, whether led by industry or the government, can also establish shared benchmarks for safety, interoperability, and performance that influence behavior.[ref 112] Government procurement power can shape markets as companies compete on the metrics set by federal agencies for what they will purchase.[ref 113] Antitrust enforcement (with remedies like divestiture) may address some concentration of power problems that regulation does not. And as consumers grow more sophisticated in evaluating AI products, market pressure alone may discipline some harms without the need for regulatory intervention.

Enforceability should weigh heavily in this assessment (discussed in subsection 5). Different tools require different enforcement capacities, and an intervention that cannot be meaningfully enforced may be worse than no intervention at all, creating the illusion of oversight while harmful practices continue or burdening compliant actors while bad actors ignore requirements.

Ultimately, the question is both “which actor should we target?” and “what kind of intervention is most likely to work?” Policymakers should not rush past these questions by assuming regulation is the solution to every problem.

III. The Where: Which Actor in the AI Ecosystem Does the Intervention Target?

The path from silicon chip to real-world harm is filled with actors that could prevent those harms. This primer organizes actors in the AI ecosystem into seven stages based on their role in the AI ecosystem: (1) chip designers and manufacturers, (2) cloud compute providers, (3) data suppliers, (4) model developers, (5) application deployers, (6) complementary and enabling platforms, and (7) end users. Each set of actors offers a potential leverage point for intervention.

These stages do not map neatly onto corporate structures: a single company can span multiple categories. Google, for example, functions as a cloud provider (Google Cloud), data supplier (via YouTube), model developer (Google DeepMind), and application deployer (Gemini). The purpose of this framework is to help policymakers regulate by the role an entity plays in the causal chain from the creation of an AI system to the materialization of harm, regardless of who performs each function.

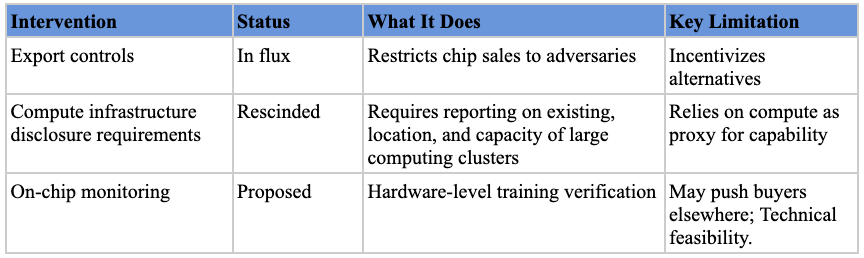

A. Stage 1: Chip Designers and Manufacturers

The semiconductor supply chain is a key intervention point for shaping AI’s development and deployment. Training and running advanced AI systems requires specialized semiconductors like Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (“ASICs”) or Graphics Processing Units (“GPUs”). These chips are designed by a handful of companies (mostly NVIDIA, AMD, Google) and produced by an even smaller number of foundries (mostly TSMC) using manufacturing equipment (extreme ultraviolet (“EUV”) lithography machines) from a single supplier (ASML). This market concentration creates chokepoints that policymakers can leverage for policy enforcement.[ref 114]

Examples of Policy Interventions

Export controls on AI chips. The U.S. government’s primary tool for shaping international AI development thus far has been export controls on advanced semiconductors, first announced in late 2022 and updated several times since.[ref 115] This policy is in flux as the Trump administration has flip-flopped on export controls for advanced AI chips to China. The most recent announcement was that NVIDIA can sell its advanced H200s to China.[ref 116]

Compute infrastructure disclosure requirements. The Biden Administration’s 2023 AI executive order (since rescinded) required entities acquiring or possessing large-scale computing clusters to report their existence, location, and total computing capacity to the government.[ref 117] This was intended to give policymakers visibility into the physical infrastructure being assembled for advanced AI training.

On-chip governance mechanisms. Researchers have proposed adding technical components to chips that would give regulators visibility into large training runs without compromising AI companies’ commercial interests.[ref 118] Though requiring further research into technical feasibility, verification mechanisms have been a prerequisite for international cooperation in other domains (like nuclear nonproliferation) and may be just as valuable for AI governance.[ref 119]

Advantages of Targeting This Stage

Focusing policy interventions on semiconductor companies has four key advantages: excludability, quantifiability, detectability, and enforcement feasibility.[ref 120]

First, computing resources are excludable because people can be prevented from accessing them. Unlike data or algorithms, which are easily copied and shared, there are a finite number of operations that a single GPU can perform. If one actor is fully utilizing those operations, no one else can.

Second, compute is quantifiable—it “can be easily measured, reported, and verified” in terms of the operations per second a chip can perform or its communication bandwidth with other chips.[ref 121]

Third, large-scale training runs are detectable. The most advanced AI models currently require large-scale training runs using thousands of specialized chips concentrated in power-intensive data centers. These facilities are detectable by third parties, with some visible from satellite imagery.

Finally, the semiconductor supply chain is extraordinarily concentrated, making enforcement feasible.[ref 122] NVIDIA controls 80-95% of the market for AI chip design; TSMC fabricates approximately 90% of advanced chips; ASML supplies 100% of the extreme ultraviolet lithography machines used by leading foundries. This concentration makes the other three advantages actionable: fewer actors makes monitoring and enforcement easier.[ref 123]

Disadvantages of Targeting This Stage

Despite these advantages, semiconductor-focused interventions have three significant drawbacks: they rely on an assumption that may not hold, they are blunt and they become less effective the more they are used.

First, semiconductor-focused regulation relies on compute serving as an effective proxy for capability. If AI performance improves such that less-than-state-of-the-art models become capable of serious harm, or if algorithmic efficiency gains reduce the compute needed for dangerous capabilities, then semiconductor-focused interventions will miss their intended target.[ref 124] Additionally, as Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor have argued, “AI safety is not a model property,” since whether an output is harmful depends on context, and capability restrictions are thus, although laudable, a misguided approach.[ref 125]

Chip-level interventions are also among the bluntest available.[ref 126] Because semiconductors are general-purpose inputs, restrictions at this stage cannot distinguish between beneficial and harmful uses of AI. Export controls that limit access to advanced chips, for example, constrain medical research and climate modeling just as much as they constrain weapons development or surveillance. Policymakers targeting this stage risk throttling AI development altogether rather than surgically addressing specific harms.

Finally, semiconductor interventions are valuable in the short term but potentially counterproductive in the long-term. On-chip governance mechanisms and export controls, while potentially controlling how chips are used or limiting adversaries’ access to them in the short term, encourage investment in alternatives. On-chip restrictions could push buyers toward more open alternatives produced in other jurisdictions. Some have argued U.S. export controls benefit China’s semiconductor industry by encouraging further investment,[ref 127] though others believe such indigenization fears are overblown.[ref 128] And geopolitical competition may prevent countries from regulating their own semiconductor industries at all, for fear of ceding a competitive edge. Finally, compute-based restrictions may encourage innovation that renders compute less likely to be a bottleneck in the future. For example, DeepSeek’s efficiency may be an unintended consequence of limiting Chinese firms’ access to computing resources, with compute constraints forcing researchers to develop more efficient algorithms.

Summary

Semiconductor-based interventions are a powerful policy tool. They work best for harms that are identifiable without much context, where a single malicious actor’s access to advanced capabilities increases risk regardless of how they’re used. They are particularly valuable when traditional enforcement is impractical—against foreign actors, in situations involving diffuse harms, or when agencies cannot possibly monitor all end users. But policymakers should be aware that these interventions are a blunt instrument that incentivize workarounds, and they depend on compute remaining a bottleneck for dangerous capabilities.

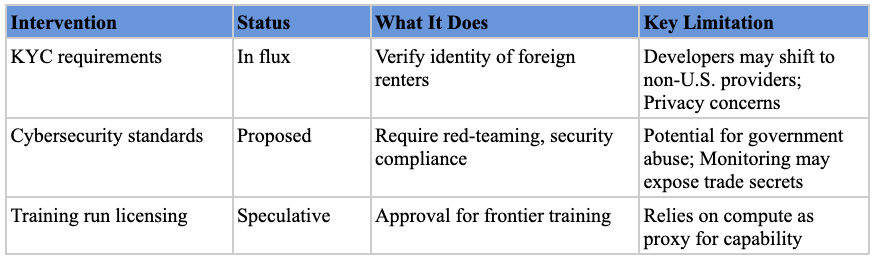

B. Stage 2: Cloud Compute Providers

A handful of cloud computing providers—Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud—operate the computing infrastructure used by most developers to train and deploy AI models. Because this stage and the previous one both focus on the computational resources underpinning advanced AI, they share many characteristics and are often grouped together under the general heading of “compute governance.” This section focuses on the ways in which targeting cloud providers differs from targeting the semiconductor supply chain.[ref 129]

Examples of Policy Interventions

Know-Your-Customer (KYC) requirements. Efforts to impose KYC obligations on cloud providers date back to Trump’s first-term EO 13984 (2021),[ref 130] which Biden’s EO 14110 (2023)[ref 131] later expanded with AI-specific reporting mandates. Providers would be required to notify the government when foreign actors access computing resources above certain thresholds, aiming to prevent adversaries from anonymously using U.S. infrastructure for dangerous AI development.

Cybersecurity compliance and AI safety standards. In 2024, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) proposed rules requiring cloud providers and their clients to report on frontier AI development activities, including compliance with cybersecurity frameworks and results of mandatory red-teaming tests.[ref 132] This would leverage cloud providers as enforcers to ensure hosted AI projects meet security benchmarks.[ref 133]

Government oversight of frontier AI training. Some researchers have recommended requiring licenses for AI training that exceeds certain compute thresholds.[ref 134] Cloud providers would require government approval before allowing training runs capable of producing frontier models—resembling licensing in the aerospace and nuclear energy industries.

Advantages of Targeting This Stage

Cloud computing shares the same fundamental advantages as semiconductor governance—concentration, excludability, quantifiability, and detectability—but offers additional benefits for regulators.

First, cloud providers’ business models already require extensive monitoring. Because they charge customers based on usage, they precisely measure resource consumption through metrics like floating-point operations, GPU hours, and energy consumption. This existing infrastructure can be repurposed for regulatory compliance with less added burden.

In addition, unlike the semiconductor supply chain, which is distributed across the United States’ allied nations, including the Netherlands, Japan, and Germany, the world’s largest cloud providers are headquartered in the United States. This gives American policymakers more jurisdictional flexibility in designing and enforcing regulations.[ref 135]

Cloud providers can also respond to non-compliance immediately. Unlike semiconductor restrictions, where there is a lag between placement on an export control list and actual business disruption, cloud access can be revoked in real time (similar to how banks can freeze accounts). This makes cloud-based enforcement more like financial regulation than trade regulation.

Disadvantages of Targeting This Stage

Cloud provider interventions share the two core weaknesses of semiconductor controls and add a third.

Like semiconductor interventions, cloud-based regulation relies on the assumption that advanced AI requires access to large compute clusters. If algorithmic efficiency improves enough that dangerous capabilities can be achieved with modest resources, then cloud-focused controls will miss their target.

Cloud restrictions also risk sparking the same kind of workarounds and indigenization that undermine export controls. Developers facing extensive compliance requirements may switch to less-regulated providers in other jurisdictions, and countries seeking AI independence or “sovereignty”[ref 136] may invest in domestic cloud infrastructure precisely to escape U.S.-based oversight. The more effective cloud controls are in the short term, the stronger the incentive to route around them in the long term.

Finally, cloud interventions also raise concerns that detailed tracking of activity on clients’ servers could expose information that companies treat as trade secrets like training techniques.[ref 137] And broad authority to cut off companies’ access to computing resources creates potential for abuse, as officials might target companies disfavored by the governing party or use access as leverage for purposes beyond AI safety.

Summary

Cloud provider interventions function as a more responsive version of semiconductor controls—enforcement can happen immediately rather than through supply-chain disruption. They are particularly valuable when real-time response matters or when tracking the identity of AI developers (rather than just their capability) is important. However, they come with greater privacy trade-offs and the same diminishing-returns problem as other compute governance approaches.

C. Stage 3: Data Suppliers

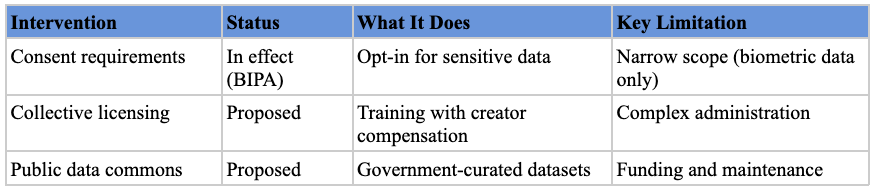

AI models are trained on data sourced from many entities: large-scale web scrapers (like C4), crowdsourced platforms (like Amazon Mechanical Turk), and specialized data labeling companies (like ScaleAI and Mercor).[ref 138] The goal of data-supplier-focused interventions is to improve the upstream collection and quality of AI training data to reduce downstream harms.[ref 139]

Examples of Policy Interventions

Individual data rights. Several states require data brokers to register with the government and disclose details about the data they collect, how it’s used, and their sharing practices. California’s Delete Act aims to allow residents to request deletion of their personal information from data brokers through a single request.[ref 140] Illinois’s Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) requires opt-in consent for entities collecting biometric data,[ref 141] significantly affecting AI facial recognition training. With AI, honoring these rights may involve removing data from supplier databases, retraining models, or filtering outputs traceable to deleted data, though the FTC has ordered complete model deletion in cases of egregious data misuse.[ref 142]

Collective licensing and compensation mechanisms. John Axhamn has proposed an “Extended Collective Licensing (ECL)” scheme that would allow AI developers to legally train on copyrighted works while ensuring rightsholders receive compensation.[ref 143] A Congressional Research Service report discusses these frameworks as potential solutions to the tension between AI training and intellectual property rights.[ref 144]

Public datasets. Governments and research institutions could create and maintain high-quality public datasets. The Trump administration’s Genesis Mission is an attempt to unify federal scientific archives into a centralized, standardized platform, democratizing AI development for smaller companies and academic researchers who lack resources to develop proprietary datasets.[ref 145]

Advantages of Targeting This Stage

Addressing data quality and legality at the point of collection and aggregation can prevent problems from multiplying as models are deployed.[ref 146]

Many data supplier regulations align with existing privacy laws like GDPR and CCPA.[ref 147] This allows policymakers to build on established definitions, enforcement mechanisms, and compliance infrastructure rather than creating entirely new regulatory regimes.

The data broker[ref 148] and AI data labeling[ref 149] industries are also relatively concentrated, allowing authorities to oversee a significant portion of data flowing into AI systems by regulating a manageable number of entities.

Disadvantages of Targeting This Stage

Data suppliers can operate globally, potentially sourcing data from or locating servers in jurisdictions with weaker regulations. AI developers might bypass rules by using offshore brokers or scraping data outside the state’s reach.[ref 150]

Defining who qualifies as a regulated “data supplier” is also difficult.[ref 151] Rules could be too narrow (missing web scrapers) or too broad (burdening nonprofits like Wikipedia or individual bloggers). And compliance costs may further consolidate the market around larger players who can afford them.

Finally, regulations restricting collection, sale, or use of data may face First Amendment challenges. The Supreme Court’s decision in Sorrell v. IMS Health held that the “creation and dissemination of information are speech,” meaning data regulations can potentially trigger heightened constitutional scrutiny.[ref 152]

Summary

Data supplier regulations are most useful for harms directly linked to data inputs—privacy violations, copyright infringement, and biased training data—and where key data sources are concentrated and identifiable. They also benefit from alignment with existing privacy frameworks like GDPR and CCPA. They are less effective when data is highly diffuse, when suppliers operate across jurisdictions, or when defining the scope of regulated entities is difficult.

D. Stage 4: AI Model Developers

This stage focuses on organizations that research, develop, and train large-scale AI models—entities like OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, Meta AI, and xAI. Given their central role in developing core AI capabilities, model developers are frequent targets for policy intervention.[ref 153]

Examples of Policy Interventions

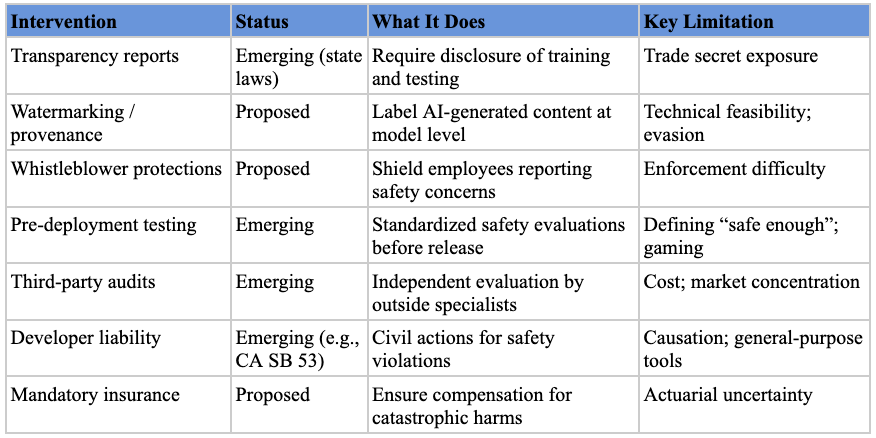

Transparency and Disclosure Mandates. The most common type of intervention at the state level promotes transparency through disclosure requirements.[ref 154] These can take several forms: requiring companies to publish reports on model development and testing processes; mandating watermarks or content provenance techniques to label AI-generated content; creating whistleblower protections for AI lab employees; and establishing incident reporting requirements for significant safety events.

Testing, Design, and Oversight Requirements. These interventions focus on ensuring safety through design mandates and ongoing oversight.[ref 155] They might include ex ante design features (cybersecurity safeguards, content filtering, “kill switches”), standardized pre-deployment evaluations, red-teaming by internal safety experts,[ref 156] or third-party audits by civil society organizations (like METR) or government agencies (like the UK AISI or US CAISI).[ref 157]

Liability frameworks. Policy researchers have advocated holding model developers liable for harms caused by their systems.[ref 158] California’s SB 53, for example, authorizes the state Attorney General to bring civil actions against developers for failure to report safety incidents or comply with their own frameworks, with damages up to $1,000,000.[ref 159] Insurance requirements could complement direct liability by ensuring compensation is available and creating actuarial signals about the riskiest models.[ref 160] For catastrophic risks, policymakers could consider ex ante mechanisms like mandatory liability insurance or industry-wide compensation funds, modeled on frameworks like the Price-Anderson Act for nuclear accidents.[ref 161]

Advantages of Targeting this Stage

Transparency measures are among the least controversial categories of model developer regulation.[ref 162] Even experts who disagree about the speed and shape of AI risks often agree on the need for more transparency.[ref 163] The rationale is that disclosure empowers users, researchers, and regulators to make informed decisions—if people know how a model was created and tested, they can better assess its reliability and risk.

Testing and oversight requirements can target vulnerabilities in base models that propagate to downstream applications. If a foundation model has a security vulnerability or can be tricked into revealing training data, applications built on top of it can inherit those vulnerabilities.[ref 164] It also leverages technical expertise outside government: regulators can set standards and review results while outsourcing the highly technical evaluation process to specialists.[ref 165]

Finally, liability incentivizes developers to prevent harms by requiring them to pay for damage caused by their models. Liability forces companies to internalize externalities rather than shifting costs to users or society. It also can function as a floor of legal protection, with some egregious AI harms likely falling within the scope of existing tort law.[ref 166]

Disadvantages of Targeting this Stage

Transparency requirements carry their own risks. Detailed disclosures about training data or architectures could expose trade secrets, allowing competitors (including foreign actors) to free-ride on research investments. Watermarking faces technical feasibility concerns: determined actors can remove watermarks, and open-source models that don’t apply them will remain unlabeled. And in the United States, compelled disclosure requirements may face First Amendment challenges as compelled speech.[ref 167]

Oversight requirements face a different problem: defining “safe enough” is extremely difficult. AI systems can fail in unpredictable ways, and any set of evaluations risks missing novel failure modes. Worse, developers might learn to game required tests, tuning models to pass evaluations without truly improving safety.[ref 168] Extensive testing requirements can also slow innovation and concentrate the market as larger, well-resourced companies absorb compliance costs more easily.

Finally, liability is limited by the fact that many AI harms are not within developers’ sole control. AI systems are general-purpose tools used in countless contexts far removed from what creators envisioned. If an open-source model is integrated into hundreds of applications, it may be unfair to blame the model’s creators for a particular application’s failure or a user’s misuse. Defining “reasonable care” for AI, determining causation when multiple actors are involved, and apportioning liability (joint and several vs. proportional) all present difficult legal questions.[ref 169] Liability also functions best when wrongdoers can afford to pay; when the defendant lacks resources or the harm is too large, liability does not fully compensate victims and is a less effective deterrent.

Summary

Model developers are a natural focal point for AI regulation because they control the foundational capabilities on which downstream applications depend. Transparency requirements enjoy the broadest support and face the lowest political barriers, though they must be designed to avoid exposing proprietary information. Testing and oversight requirements can catch vulnerabilities before they propagate downstream, but they must be iteratively adjusted as capabilities evolve—static evaluations will quickly become obsolete. Liability frameworks complete the picture by internalizing costs, but their effectiveness depends on resolving difficult questions about causation, apportionment, and the financial capacity of defendants to pay for harms their models enable.

E. Stage 5: Application Deployers

The application layer is where AI capabilities are operationalized into products and services. The entity developing the model can also be the deployer (OpenAI’s ChatGPT is built on its GPT models), but different companies can also build applications on top of models developed by others. Applications span nearly every sector: predictive algorithms for employment screening (HireVue, Pymetrics) and criminal justice risk assessments (COMPAS); generative models powering chatbots (Character.ai) and coding environments (Cursor); and agentic systems capable of completing tasks without human intervention (Claude Code, Devin).

Examples of Policy Interventions

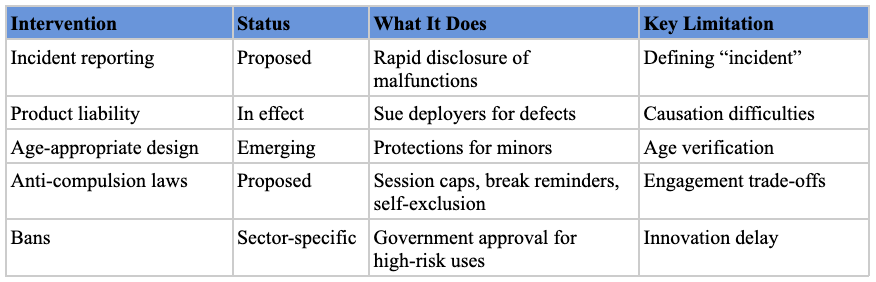

Incident reporting. When AI applications malfunction or cause harm, rapid disclosure enables regulators and the public to identify patterns and respond before problems spread. Analogous requirements exist across regulated industries: the FDA mandates adverse-event reporting for medical devices, NHTSA requires crash reporting for autonomous vehicles, and the FAA tracks near-miss incidents in aviation. Extending this model to AI deployers would require companies to notify a designated agency when their systems produce significant failures—whether a hiring algorithm systematically excludes qualified candidates or a medical diagnostic tool generates dangerous misdiagnoses. The core difficulty is defining what counts as a reportable “incident” for general-purpose AI systems that operate across diverse contexts.

Tort liability. Application deployers are also potential targets for liability.[ref 170] Injured parties can sue the deployer for compensation if a particular application causes harm. One mother, for instance, sued Character.AI over her son’s suicide, alleging design defects.[ref 171] In a separate case, the parents of a sixteen-year-old sued OpenAI, alleging that ChatGPT acted as a “suicide coach” that encouraged their son’s suicidal ideation.[ref 172] The possibility of liability creates incentives to build safe products. Legislatures can play an important role in ensuring this system functions well. California’s AB 316, for example, is a recently enacted bill that aims to ensure there is no AI exception to existing tort liability frameworks.[ref 173] It prevents defendants from disclaiming responsibility by arguing that an AI agent acted autonomously.[ref 174] Legislatures could also codify duties of care rather than leaving courts to define them through the common-law process.

Age restrictions. These provisions require deployers to implement age-appropriate design for systems used by minors, including limiting data collection, obtaining parental consent, and requiring plain-language explanations. Texas’s SCOPE Act (2024) offers a comprehensive template: it requires parental consent before minors can create accounts, prohibits in-app purchases and geolocation tracking for minors, bans targeted advertising to children, and mandates content filtering for material promoting self-harm, substance abuse, or exploitation.[ref 175] This approach is valuable because it shifts the compliance burden onto platforms rather than parents, creating structural protections that don’t depend on individual digital literacy or vigilance.

Self-exclusion. These statutes require deployers to build protective features into products—such as session caps, break reminders, and disabling infinite scroll—that help users limit their own consumption. The UK Gambling Commission’s “reality check” regulations provide a direct model:[ref 176] operators must display recurring on-screen reminders of elapsed session time that users must actively acknowledge before adding new funds,[ref 177] and the UK has banned autoplay features entirely while mandating time intervals between interactions.[ref 178] This framework is valuable because it acknowledges that willpower alone may be insufficient against products engineered for engagement, and it creates friction that can help users close the gap between what they want and what they want to want.

Outright bans. In contexts where AI is deemed too dangerous, policymakers might prohibit its use entirely. The U.S. Space Force temporarily banned generative AI based on security concerns.[ref 179] Several cities have banned law enforcement use of facial recognition based on privacy concerns.[ref 180] Illinois recently banned AI therapy chatbots out of concern for user safety.[ref 181] Recently proposed legislation in Tennessee would make it a felony to train a language model to “provide emotional support, including through open-ended conversations with a user.”[ref 182]

Advantages of Targeting This Stage

Regulating at the application layer gives lawmakers maximum context about AI-related harms. Because deployers operate in defined settings, regulators can set outcome-oriented requirements (i.e., maximum error rates for medical diagnosis or bias thresholds for hiring) and verify through real-world data that requirements are reducing harms.

This approach strongly aligns with existing regulatory expertise. Sector agencies like the FDA, NHTSA, EEOC, and SEC already police safety and integrity within their domains. Extending their mandates to cover AI-enabled products leverages existing staff, testing protocols, and enforcement tools. In many cases, new legislation may not be required because existing sector-specific laws and agency authorities can be applied to AI.

Disadvantages of Targeting This Stage

Effective application-layer intervention requires coordinating across many industries, each with its own stakeholders and lobbyists who may resist oversight. While sector-specific legislation may be more precise, policymakers may prefer omnibus “AI bills” for political reasons, since a single high-profile bill can yield greater electoral rewards than piecemeal legislation.

Even with political will for sector-specific regulation, different agencies crafting different rules creates fragmentation. AI applications that don’t fit neatly into existing categories may slip through gaps. Products crossing regulatory boundaries—a health chatbot handling both insurance questions and medical advice—may face overlapping or conflicting obligations.

A further concern is regulatory capture. Sector regulators develop close relationships with the industries they oversee; over time, this can blunt enforcement or slow rule updates as technology evolves.

Summary

The application layer is one of the most promising regulatory targets because deployers operate in concrete settings where harms are observable and measurable, and because many enforcement agencies—the FTC, EEOC, FDA, NHTSA—already have authority to regulate AI-related activities without new legislation. It is less effective when products span multiple regulatory domains, creating gaps and inconsistencies between agencies.

The least-cost-avoider principle is useful here: deployers who control application design and the context in which AI capabilities reach users should bear responsibility for design flaws and foreseeable failures, while liability for sophisticated misuse that deployers could not reasonably anticipate or prevent should shift to end users.

F. Stage 6: Complementary and Enabling Platforms

Platforms are often essential for translating digital outputs into real-world consequences. E-commerce marketplaces like Amazon facilitate physical goods purchases; gig economy platforms like TaskRabbit connect requesters with workers who perform physical tasks; social media networks like Meta distribute content to mass audiences. While these platforms may not develop AI themselves, they can serve as essential channels through which AI-enabled harms materialize. A language model requires access to enabling infrastructure to purchase precursor chemicals, hire a courier, or broadcast disinformation.

This intermediary role makes enabling platforms uniquely important for AI governance. They represent the last major chokepoint before harm occurs, operating at the boundary between digital intent and physical or social consequence.

Examples of Policy Interventions

E-commerce and Procurement Platforms

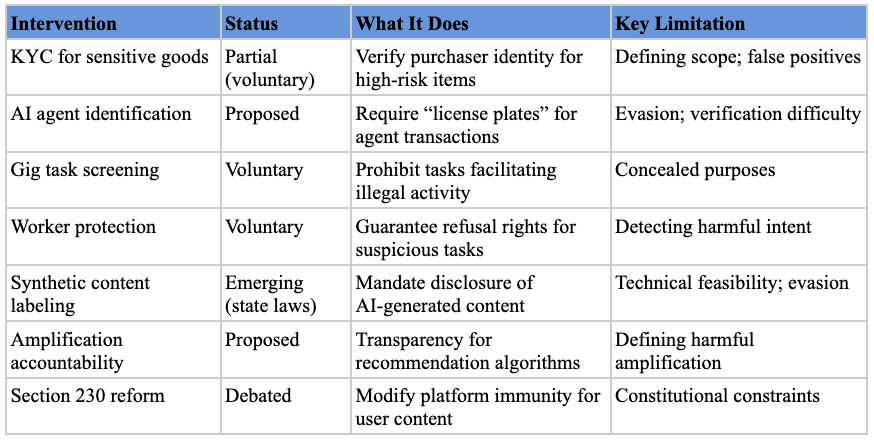

Know-Your-Customer and suspicious activity reporting. Platforms could be required to verify purchaser identities for certain categories of goods (chemicals, laboratory equipment, dual-use materials) and report suspicious purchasing patterns to relevant authorities, similar to banking regulations under the Bank Secrecy Act.[ref 183]

AI-aware transaction monitoring. As AI agents gain the ability to autonomously browse and purchase goods, platforms may need new detection mechanisms. Jonathan Zittrain has proposed that AI agents carry identifying credentials—akin to “license plates”—that would allow platforms to apply heightened scrutiny to agent-initiated transactions, particularly for sensitive goods categories.[ref 184]

Gig Economy and Labor Platforms

Task screening and identity verification. Platforms like TaskRabbit, Fiverr, and Upwork could be required to maintain explicit prohibitions on tasks that facilitate illegal activity—delivering unknown substances, conducting surveillance, accessing restricted areas—and to require enhanced identity verification for task categories with higher abuse potential.

Worker protection and refusal rights. Gig workers may be unwitting participants in harmful schemes.[ref 185] Regulations could guarantee workers the right to refuse suspicious tasks without penalty and require platforms to maintain reporting channels for workers who suspect they are being used for illicit purposes.[ref 186]

Social Media and Content Distribution Platforms

Synthetic content labeling requirements. Building on recent state laws, policymakers could mandate that AI-generated content be labeled when distributed on social media,[ref 187] including technical standards for embedded metadata (such as C2PA provenance standards)[ref 188] and disclosure requirements for accounts that post primarily AI-generated content.[ref 189]

Amplification accountability. Beyond content moderation, platforms could face obligations related to algorithmic amplification—transparency requirements for recommendation algorithms, prohibitions on amplifying content that violates platform policies, or duties to detect coordinated inauthentic behavior.

Section 230 reform. The most significant potential intervention involves modifying Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which currently immunizes platforms from liability for user-generated content.[ref 190] Reform proposals range from narrow carve-outs (removing immunity for algorithmically amplified content) to broader conditions (requiring reasonable content moderation as a prerequisite for immunity).[ref 191]

Advantages of Targeting This Stage

These platforms represent the final major chokepoint before harms materialize. Even if upstream interventions fail, enabling platforms can still prevent the final step. A bioweapon cannot be synthesized without ingredients; an influence campaign cannot succeed without distribution.

Additionally, unlike AI-specific entities, enabling platforms already operate under extensive regulatory frameworks (e.g., consumer protection laws, export controls, anti-money-laundering rules). Extending these frameworks to address AI-enabled harms leverages established compliance capabilities.

Finally, platform intermediation creates records that facilitate both ex ante screening (flagging suspicious patterns) and ex post investigation (reconstructing how harm materialized).

Disadvantages of Targeting This Stage

The sheer volume of platform activity is the first challenge. Major platforms process billions of transactions.[ref 192] Any screening system will produce false positives and false negatives; at scale, even low error rates translate into millions of affected transactions.

Even with effective screening, platforms often cannot determine whether a transaction is AI-enabled. Without reliable signals distinguishing human from agent activity, platforms cannot easily apply differential scrutiny.[ref 193] Requiring AI disclosure depends on the honesty of precisely those actors least likely to comply when pursuing harmful ends.

Content-related interventions face an additional obstacle. For social media platforms, content-based regulations face significant constitutional scrutiny under the First Amendment. Requirements to remove or label certain categories of speech must be narrowly tailored to compelling government interests.

Finally, users seeking to evade restrictions can shift to less-regulated platforms, international services, or decentralized alternatives like cryptocurrency marketplaces or federated social networks.

Summary

Enabling platforms are most valuable as intervention targets when harms require real-world resources or distribution that platforms mediate. They are the last major chokepoint where harms can be intercepted, and they benefit from existing compliance infrastructure that can be extended to AI-specific concerns. Platform-level interventions are less effective when users can easily shift to unregulated alternatives; they also face significant First Amendment constraints for content-related regulations. The least-cost-avoider principle suggests platforms should bear responsibility for harms they are well-positioned to prevent: suspicious purchasing patterns, task requests that facially violate policies, and content that clearly meets removal criteria. But platforms are not well-positioned to prevent harms requiring information they lack or judgment calls they cannot reliably make at scale.

G. Stage 7: End Users

End users are the final actor in the AI ecosystem. Institutional users like businesses and government agencies embed AI tools into existing workflows, often under sector-specific laws. Individual users typically lack formal compliance programs or resources to vet AI systems, yet their choices can still inflict measurable harm and are subject to liability under the tort system.[ref 194]

Examples of Policy Interventions

Organizations Using AI

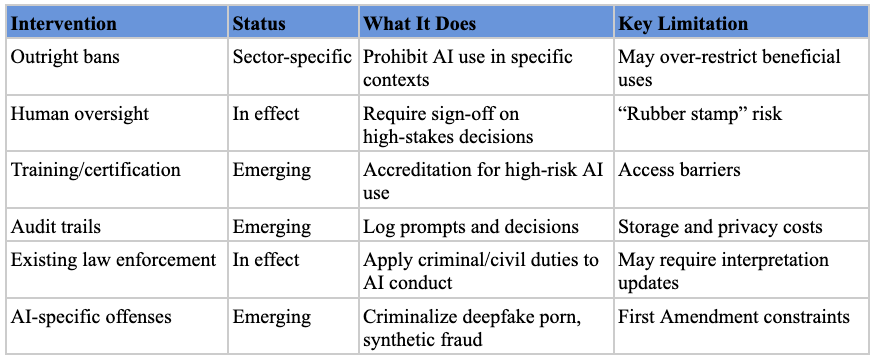

Human oversight requirements. These require qualified people to oversee or override AI predictions.[ref 195] A bank using predictive AI for loan approvals might require a human loan officer to sign off on high-stakes decisions. The idea is that human oversight provides a fail-safe to catch errors or bias that AI systems might miss, though there are compelling critiques that people might simply rubber-stamp AI decisions.[ref 196] They are also called “human-in-the-loop” requirements.

Training and certification. Hospitals, financial firms, or law enforcement agencies might be required to obtain accredited licenses or complete mandated coursework before deploying high-risk AI systems.

Record-keeping and audit trails. Organizations may need to log prompts, outputs, and decision rationales so regulators or litigants can reconstruct how harmful decisions occurred.

Individuals Using AI

Use existing tort law to find liability. Many harms individuals can inflict with AI—hacking, defamation, malpractice—are already covered by criminal statutes, tort principles, or professional ethics rules.[ref 197] Even if the tool changes (AI), the duty does not. For example, a lawyer must still verify citations whether they come from Westlaw or a language model. State attorneys general and other entities authorized to enforce laws can reinforce this through guidance and sanctions without creating new technology-specific offenses.

Create AI-specific duties for genuine gaps. Where existing law does not squarely address new harms, legislatures can craft targeted rules—criminalizing non-consensual AI-generated intimate imagery or requiring disclosure for synthetic political ads depicting candidates saying things they never said.[ref 198]

Advantages of Targeting This Stage

End-user liability puts accountability on the actor often best positioned to prevent harm. The individual or organization that chooses to post a deepfake, ignore a safety warning, or rely blindly on AI output controls the immediate risk and can avoid it at low cost—by double-checking facts, limiting sensitive prompts, or declining to deploy AI in high-stakes contexts.

Focusing sanctions at the user layer also protects upstream innovation. Model developers and application builders can continue releasing general-purpose tools without bearing the full weight of every possible downstream abuse, because liability attaches only when users turn tools toward prohibited or negligent uses.

Finally, user-level liability also carries expressive value. By singling out certain AI-enabled acts as punishable—non-consensual synthetic pornography, fraudulent legal filings, deceptive political ads—the law signals which uses of AI violate shared norms, helping shape social expectations in a fast-moving technological landscape.

Disadvantages of Targeting This Stage

End-user liability is inherently retroactive: it activates only after harm has occurred. For irreversible injuries—viral deepfakes that permanently taint reputations, election disinformation that cannot be “un-voted,” psychological trauma from non-consensual intimate images—damages or takedowns arrive too late to help those already harmed.